News

Issues Interviews Order

About Follow

Support Submit

Contact ©MONU

16-10-23 // NEW ISSUE: MONU #36 - NEW SOCIAL

URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #36 here.

(browse

the entire issue #36 on Youtube)

Vulnerable City by Maria Reitano; Free Floating Fascism and

Religious Revanchism is The New Neoliberalism by Mark Gottdiener;

Social

by Definition - Interview with Sharon Zukin by

Bernd Upmeyer; Density, Equity, and Epidemics in New York City

by Richard Plunz and Andrés Álvarez-Dávila; Do

Nothing for as Long as Possible by Tatjana Schneider; The Life

Within Buildings: Towards a New Housing Policy by Christoffer Jusélius

and Helen Runting; Unforgetting the Public City by Constanze Wolfgring;

New Rights, New Needs, New Rules by Nuria Ribas Costa; Spatial

Reappropriation through Transformative Practices by Valentina Rizzi;

New I Am by Bharat Sikka; Post-Public Space by Francisco Silva;

Technology as Medium to Rethink Spatiality by Tatjana Crossley;

From the Global Village to the Global Home by Serafina Amoroso;

2091: The Ministry of Privacy by Maxime Matthys; The Strange Bedfellows

of Contemporary Urbanism by Brian Holland; San Francisco: From

“Ghost Town” to a New Social City? by Agnes Katharina Müller;

Between

the City and the Family - Interview with Izaskun Chinchilla by

Bernd Upmeyer; The Opportunity for Joyful Cities by Paul Kalbfleisch;

The Municipal Services Buildings of Hong Kong by Ying Zhou; Navigating

the Work Morphology Shift: A New Perspective on Social Urbanism by Mingming

Zhao

How

is a “New Social Urbanism” possible if the hegemonic Western

paradigm of space production revolves around the antisocial principle of the

individualization of every aspect of life? asks Maria Reitano

in her piece “Vulnerable City”. According to her, long before,

during, and after the pandemic, individualization and competitiveness define

the (anti)social consistence of the Western neoliberal city. Following Mark

Gottdiener and his contribution “Free Floating Fascism and Religious

Revanchism is The New Neoliberalism: Challenges for Architects and Urban Planners”

we have entered a new phase of global destabilization amplifying social deficits

after Neoliberalism’s dismantling of social institutions has been shown

to have critically injured the structure of society leading to aggravated and

extreme social problems. Sharon Zukin, too, is rather pessimistic about whether

a “New Social Urbanism” is rising, as she states in our interview

with her called “Social by Definition”, pointing out that even

cities like New York are increasingly unable to pay for and to respond to people’s

needs for housing, healthcare, and education. Richard Plunz and

Andrés Álvarez-Dávila confirm the dire housing

situation in their article “Density, Equity, and Epidemics in New York

City”, in which they emphasize that, after numerous attempts, the economics

of housing production in New York today shows no capacity for producing affordable

housing and that the most recent health crisis has only aggravated pre-existing

socio-economic and racial disparities in housing insecurity. However,

Tatjana Schneider challenges us in her contribution “Do Nothing

for as Long as Possible” to engage with what causes these conditions,

arguing that the critique is there, the analysis too, and that there are therefore

hopeful rifts and cracks. Because we already have many of the tools and the

infrastructures needed to challenge the unequal, cynical, and anti-social system

in which we operate as planners, as Christoffer Jusélius

and Helen Runting clarify in “The Life Within Buildings:

Towards a New Housing Policy”, but what we do not have - yet - is the

collective will to fully utilize these resources. That is why we need to revive

a sense of solidarity and shared responsibility, an ethics that constitutes

a necessary foundation for the hard work that will be needed to create inclusive

cities. Nuria Ribas Costa reminds us in her article “New

Rights, New Needs, New Rules” that such ethics can be stimulated and

supported by the implementation of collaborative and grassroots conflict-solving

and decision-making institutions, as “New Social Urbanism”

is not only about how the city is lived, but also how it is owned and governed.

Thus, envisioning a “New Social Urbanism” requires a thoughtful

consideration of participatory co-constructed strategies that revitalize the

urban and social fabric, providing an organic pathway for community development,

as Valentina Rizzi puts it in “Spatial Reappropriation

through Transformative Practices”. Her research presents case studies

that intervene in the urban realm by combining visual arts and performative

arts with the architecture of bodies and spaces, aiming to create transformative

experiences of rupture, experiences that are mysteriously graspable in the images

of Bharat Sikka’s series of photos entitled “New

I Am”. But today our urban realm and our public spaces have expanded

due to recent technological progress into the digital domain too, enabling possibilities

for human relationships that were once out of reach as Francisco Silva

points out in “Post-Public Space”. According to him, social

spaces can become places of reunion that are driven by a design focused on the

complexity of the human connection. In a merger of body, technology, and all

the structures that surround them, public spaces may finally find a tabula rasa

that allows them to return to their very essence - the pleasure of connection.

By uploading the photographs of the everyday lives of the inhabitants of one

of the last remaining bastions of Uyghur culture in Kashgar into facial recognition

software and by rendering the resulting biometric data directly onto the subjects’

faces, Maxime Matthys illustrates with his project “2091:

The Ministry of Privacy” what such a merger of body, technology, and

surrounding structures might look like. One way of understanding mergers like

these is through the concept of hybridisation. To do so, Brian Holland

introduces in his piece “The Strange Bedfellows of Contemporary Urbanism”

practices to which he refers as “piggybackings” that at their best

create surprising entanglements that provoke hybrid forms and programs of social

exchange capable of promoting greater equity and diversity in the built environment.

For Holland the piggybacking practices that he presents illuminate

an important form of social entrepreneurialism in contemporary urban life contributing

to a “New Social Urbanism”. When asked about the future of

social urbanism, Izaskun Chinchilla, too, believes that we are

heading toward a hybrid situation in which we will socialize both physically

and digitally, multiplying the spectrum of the ways of meeting and socializing,

as she explains in our second interview entitled “Between the City and

the Family” stressing the importance of the neighbourhood for a “New

Social Urbanism”. And as the demarcation between home and work increasingly

dissipates, architects, urban designers, and urban planners might be motivated

to conceive more “third spaces” in cities, which are public locations

equipped with amenities to serve as communal workspaces, from parks and libraries

to cafes and community hubs, as Mingming Zhao forcasts in “Navigating

the Work Morphology Shift: A New Perspective on Social Urbanism”.

She envisions a decentralized city, where technological progression and human

comfort are intertwined, shaping an urban environment that feels simultaneously

futuristic and familiar. We never know what new forms will emerge out of that,

although if you think about democracy in a city as a role model, it is always

very messy, as Zukin states, but according to her this may be

what “New Social Urbanism” is all about.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2023

(Cover: Image is part of Maxime Matthys’ contribution “2091:

The Ministry of Privacy” on page 84. ©Maxime Matthys; Music: Queen

- I Want to Break Free, Video editing: Danae Zachariaki)

This

issue is supported by The

Berlage - The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban

Design; From

‘Urban Andes’ to ‘Politics in the City’! New Architecture

& Urban Planning Books from Leuven University Press; Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City: A 12-week full-time Education Programme on

Contemporary Urbanism, Dealing with Right to the City, Climate Change and Superdiversity;

and

Incognita’s Architecture

Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism. Find

out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

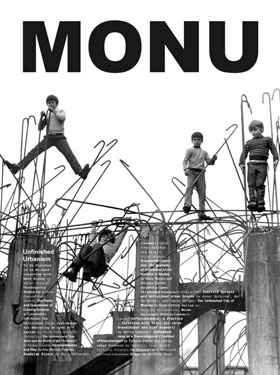

17-10-22

// MONU #35 - UNFINISHED URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #35 here.

(browse

the entire issue #35 on Youtube)

To Be Finished Is to Be Dead -

Interview with Mark Wigley by Bernd

Upmeyer; Overdesign Is a Problem Too by Marco Enia and Flavio

Martella; The Perks and Quandaries of Coming Undone a Conversation

with Akoaki; The Unfinished City: Approaches for Embracing an Open Urbanism

by Nick Dunn and Dan Dubowitz; The Architectural Non-finito and the

Death of the “Architect” by Wijdane Esseffah; Incompleteness

and Play by Ana Morcillo Pallares; Roadside Picnic - Remote Detour

around the World’s Unfinished Nuclear Power Plants by Paul Cetnarski;

Unsettled by Isabelle Pateer; California City by Elian

Somers; Suspended Urbanities: The Spatiality of Unfinished Architectures

in Naples by Maria Reitano and Nikolaus Gartner; Stranded in Limbo:

25 Unfinished Structures by MARS at PBSA; Concrete Sprouts and

Unfinished Urban Dreams by Avsar Gürpinar, Nur Horsanal, and Cansu

Cürgen; The ‘Unfinished’ City of Mumbai by Rupal

Rathore; Hellas by Maarten Willemstein; Becoming Unstuck:

Streets as Gardens, with the Disposition for Ongoing Experimentation by

Dan Hill; Unfinishedness, a

Practice - Interview with bplus.xyz (Arno Brandlhuber and Olaf Grawert) by

Bernd Upmeyer; Unfinishedness as a Transcategorial Condition of Abandonment

by Tiphaine Abenia; The Unfinished Interior by Marcello Carpino

and Vittoria Poletto; The Temporal City by Ian Nazareth and David

Schwarzman; Ordos by Anthony Reed

“To Be Finished Is to Be Dead” claims Mark Wigley

in our interview with him. Because only an unfinished city is a city that is

open to unknown and unpredictable transactions and that is what cities are for.

To him, urbanism is only urbanism to the extent that it is unfinished and “Unfinished

Urbanism” an urgent call in an age of a pandemic and of predictability,

both of which are killing us. According to Marco Enia and

Flavio Martella a living city can actually never be finished, because

by their very nature cities are unfinished organisms. As long as they are home

to a living community, cities will constantly readjust to meet its needs and

desires and only stop changing when they start to decay and vice versa. “Unfinishedness”

allows for complex forms of appropriation and participation, creating a stronger

bond with the city as they state in their contribution “Overdesign Is

a Problem Too”. Thus, only with an open urbanism that is intentionally

incomplete can we design cities that are equitable and sustainable as Nick

Dunn and Dan Dubowitz describe the idea in their piece

“The Unfinished City: Approaches for Embracing an Open Urbanism”.

If cities are overly finished and too confined they stagnate and exclude, sharpening

further existing inequalities while simultaneously using up precious resources,

which is ludicrous in an era of climate emergency. To avoid this we need to

support the creativity of the authentic (the “uncompleted”) as opposed

to the rampant creativity of the exact (the completed) explains Ana Morcillo

Pallares in her article “Incompleteness and Play”.

She recalls an ethos pushed by a cohort of Italian architects and designers

active from the late 1960s through the 1970s who were known as the Italian Radical

Architecture and who tried to overcome the urbanistic failures of the “completed”

plans of the 20th century through talking, listening and social practice. However,

following the arguments of Paul Cetnarski in his piece “Roadside

Picnic - Remote Detour around the World’s Unfinished Nuclear Power Plants”

we reached a point in our civilisation where certain elements of our built environment

cannot be erased, making “Unfinished Urbanism” more of a burden

than an achievement. As a result, the uncertainty of “unfinishedness”

can endanger the lives and existences of people in urban areas too as Isabelle

Pateer shows in her photo-essay “Unsettled” in which

she investigates the evolution of the Antwerp harbour expansion zone in Belgium

illustrating how the inhabitants, their environment and surroundings, as well

as their social fabric are affected by these large alterations. Therefore,

“Unfinished Urbanism” can cause many problems too, especially

when architectures become abandoned ruins within construction sites waiting

for someone to finish them as Maria Reitano and Nikolaus

Gartner point out in “Suspended Urbanities: The Spatiality of

Unfinished Architectures in Naples”. They argue that when no urban

strategies deal with such unfinished architectures – which has been referred

to as “Incompiuto” and even as a new Italian architectural style -

they become inaccessible, turning into spatial gaps, interruptions within the

urban fabric and the peri-urban landscape, and fragmenting the urban public

space. Yet Maarten Willemstein, in his series of images entitled

“Hellas”, shows similar unfinished architectures, though in Greece.

He does not want to present them merely as dilapidated buildings, but as echoes

of the old classical Greek temples and as structures that are at the beginning

of their ‘life’, neither as abandoned ruins nor at the end of their

existence providing hope for a possible future. Such optimism when it comes

to ‘ruins’ is shared by bplus.xyz (Arno Brandlhuber and Olaf

Grawert), who introduce “Unfinishedness, a Practice” in

our second interview: the possibility of a new urban regulation that does not

differentiate between office, housing, or commercial functions anymore, but

considers buildings as so-called ‘intelligent ruins’ that are thought,

designed, and built in a way to be adapted and reused in the future, enriching

the discussion on architecture and “unfinishedness” on a legislative

level. Through such functional resistance, Tiphaine Abenia sees

a hopeful disconnection and an invitation to reconcile “unfinishedness”

with a practice of freedom. Like Willemstein she is not interested

in the aesthetical fascination and romanticising of decay, which tends to freeze

the phenomenon into a necrotic image, but in the dynamic process inherent in

abandonment. In other words, she is interested in its “unfinishedness”

as she declares in “Unfinishedness as a Transcategorial Condition of

Abandonment”. Consequently, “Unfinished Urbanism”

might further reconcile the known and the unknown as Ian Nazareth

and David Schwarzman conclude in their contribution “The

Temporal City” creating spaces in which people according to Anthony

Reed and his contribution “Ordos” might feel estranged

but never lost.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2022

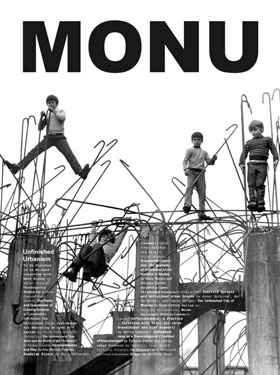

(Cover: Image is part of

Ana Morcillo Pallares’s contribution “Incompleteness and Play”

on page 39. Photograph by Riccardo Dalisi (Courtesy of Archivio Dalisi /

Napoli, Italy) Music: Limahl - Never

Ending Story, Video editing: Danae Zachariaki)

This

issue is supported by The

Berlage - The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban

Design; Estonian

Academy of Arts (EKA): Urban Studies MSc; KU

Leuven’s Master of Human Settlements and Master of Urbanism, Landscape

and Planning; Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City:

Dirty Old Town; Learning From Rotterdam - A Unique 12-week Post Graduate Education

Programme; and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

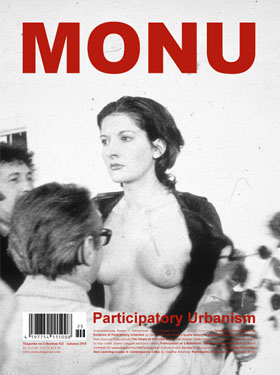

18-10-21

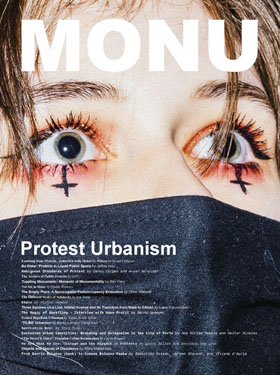

// MONU #34 - PROTEST URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #34 here.

(browse

the entire issue #34 on Youtube)

Learning from Protests - Interview

with Mabel O. Wilson by

Bernd Upmeyer; Be Water: Protests in Liquid Public

Space by Jeffrey Hou; Ambiguous Standards of Protest by

Cansu Cürgen and Avsar Gürpinar; The Archive of Public

Protests by APP; Toppling Monuments: Moments of Monumentality

by Ben Parry; Not Set in Stone by Maddy Weavers;

The Empty Plaza: A Socio-spatial Post-occupancy Evaluation by

Dillon Webster; The Different Scales of Solidarity by Ece

Yetim; Khaos by Ulrich Lebeuf; Three Squares

on a Line: Istiklal Avenue and Its Transition from State to Citizen by

Liana Kuyumcuyan; The Magic

of Squatting - Interview with Hans Pruijt

by Bernd Upmeyer; Protest Repellant Urbanism by

Nurul Azreen Azlan; 'TO-BE' Urbanism by Becky Luk and Ching

Kan; Revolution Now! by Bing Guan; Contested

Urban Identities: Branding and Antagonism in the City of Porto by Ana

Miriam Rebelo and Heitor Alvelos; "The Street Is Ours":

Feminine Urban Reclamation by Cécile Houpert; We

Are What We Are: Chicago and the Paradox of Protests by Aaron Kalfen

and Benjamin van Loon; Objects and Spaces of Dissidence by

Mario Matamoros; From Barrio Bolaños (back) to Comuna Bolaños

Pamba by Sebastián Oviedo, Jeroen Stevens, and Viviana d'Auria

Even though

our social media age marks a shift in form and forum, when it comes to "Protest

Urbanism" there still seems to be a need for - and validity of - having

physical bodies in a public space in order for a protest to have an effect,

as Mabel O. Wilson argues in our interview "Learning from

Protests". Bodies occupying large spaces or marching through different

types of arteries, be it streets or freeways, still appear to be central tactics

for people engaging in political protest. It is the visceral encounters in physical

spaces that trigger deeper and more emotional connections as Jeffrey Hou

states in his contribution "Be Water: Protests in Liquid Public

Space". For Cansu Cürgen and Avsar Gürpinar

physicality matters too as they demonstrate in their piece "Ambiguous

Standards of Protest", introducing real objects of protest into the

discussion, such as bananas, hoodies, bras, and cloth hangers that became the

symbols of the abortion protests in Poland in 2016. According to them these

objects set the ambiguous standards of protest, becoming objects of Protest

Urbanism. In APP's photo-series "The Archive of Public

Protests" we get a glimpse of how objects such as cloth hangers were

actually used during the Polish protests, which became the largest protests

in the country's contemporary history. Being part of a printed "Strike

Newspaper" the photographs can become a banner in your hand, a poster on

a building, or a picture on a wall providing tangible objects, thus offering

more than just internet circulation and silent contemplation. However, as Ben

Parry points out in "Toppling Monuments and Moments of Monumentality",

protests often gather force at the global scale especially via the creation

and circulation of powerful media images, Internet memes, and creative expressions

of solidarity leading to powerful relations between physical public space and

digital public space - the traditional and electronic agora. On the other hand,

the notion of designing physical public spaces for protests might require a

critical review, Dillon Webster demands in "The Empty

Plaza: A Socio-spatial Post-occupancy Evaluation", as protests mostly

happen with no regard to, and likely consciously against, intentionally allocated

spaces for activism. In his article he presents an example of how designs were

rejected by protesters revealing that protests are an improvisational performance

in which actors respond to temporal and physical cues, collectively reaching

a destination. With his dark and grainy images of the French Yellow Vests protests

Ulrich Lebeuf tries in his piece "Khaos" to review

the perception of protests too, aiming to rewrite history and not only to inform

but also to question. An answer to the question of how urban spaces and even

city planning might be influenced by protests is provided by Hans Pruijt

in our second interview called "The Magic of Squatting" showing

how squatting as a form of protest and as "direct action" achieved

to preserve the 19th-Century street grid of a neighbourhood in Amsterdam changing

the urban planning of the city accordingly. In the interview Pruijt

further emphasises the important role architects, urban designers, urban planners,

and other stakeholders in our cities can play in shaping, defining, and limiting

protests. He sees a particularly strong connection between architecture and

squatting in a squatted old salami factory called "Metropoliz" on

the outskirts of Rome. To what extent cities can shape or repel protests and

how the very materiality of urban space may be employed to suppress dissent,

is examined by Nurul Azreen Azlan in her piece "Protest

Repellant Urbanism" pointing out the example of Baron Hausmann's restructuring

of the Parisian urban form. Hausmann's big boulevards that cut through the medieval

urban fabric had made it difficult for protesters to build barricades, that

infamous spatial tactic synonymous with the revolutions in Paris, while making

it easier for the police to disperse the crowds. Notwithstanding the power of

cities, according to Becky Luk and Ching Kan protests

can become breeding grounds for the evolution of urban agencies, as they explain

in "'TO-BE' Urbanism". The urban agencies that emerged especially

in Hong Kong demonstrate how un-addressed and un-fulfilled claims from protests

can readily transform into the most persistent and adaptable energy for long-term

urban action. Their creation becomes an infrastructure to counter the existing

system and co-create a more democratic system for urban production. In that

way protests can serve fundamental democratic functions, as Aaron Kalfen

and Benjamin van Loon put it in "We Are What We Are: Chicago

and the Paradox of Protests" analysing how protests function as organisms

within the larger urban theatre. Following Sebastián Oviedo,

Jeroen Stevens, and Viviana d'Auria in "From

Barrio Bolaños (back) to Comuna Bolaños Pamba" Protest

Urbanism emerges thus ideally not merely as protest against a certain form

of authoritarian urbanism, nor as simply a spatial form of opposition, but as

a highly heterogeneous call for the reconstitution and recognition of fundamentally

'plural' and relational forms of making and inhabiting the city.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2021

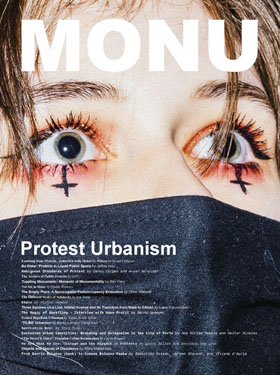

(Cover: Image is part of APP’s contribution “The Archive

of Public Protests” on page 30. ©Rafal Milach)

This

issue is supported by

Material District´s

Book: Tomorrow’s Timber, Lucerne

University of Applied Sciences And Arts: Master Studies in Architecture in Switzerland,

Estonian

Academy of Arts (Eka): Urban Studies MSc, Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City: Dirty Old Town; Act Now! - A Unique 12-week

Post Graduate Education Programme, and University

of Basel: Master of Arts - Critical Urbanisms. Find out more about MONU's

supporters in Support.

19-10-20

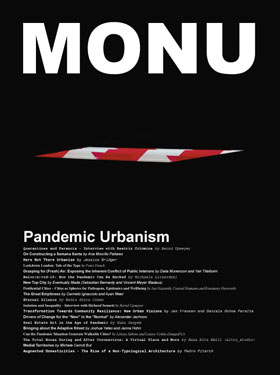

// MONU #33 - PANDEMIC URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #33 here.

(browse

the entire issue #33 on Youtube)

Quarantines and Paranoia - Interview with Beatriz Colomina by Bernd

Upmeyer; On Constructing a Semana Santa by Ana Morcillo Pallares;

Here Not There Urbanism by Jessica Bridger; Lockdown London:

Tale of the Tape by Peter Dench; Grasping for (Fresh) Air: Exposing

the Inherent Conflict of Public Interiors by Dalia Munenzon and Yair

Titelboim; Balco(n)vid-19: How the Pandemic Can Be Hacked by Michaela

Litsardaki; New Top City by Eventually Made (Sebastian Bernardy

and Vincent Meyer Madaus); Pestilential Cities - Cities as Spheres for

Pathogens, Epidemics and Wellbeing by Ian Nazareth, Conrad Hamann and

Rosemary Heyworth; The Great Emptiness by Carmelo Ignaccolo and

Ayan Meer; Eternal Silence by Nadia Shira Cohen; Isolation

and Inequality - Interview with Richard Sennett by

Bernd Upmeyer; Transformation Towards Community Resilience: New Urban

Visions by Jan Fransen and Daniela Ochoa Peralta; Drivers of Change

for the "New" in the "Normal" by Alexander Jachnow;

Real Estate Art in the Age of Pandemic by Kuba Snopek; Bringing

about the Adaptive Street by Joshua Yates and Janna Hohn; Can

the Pandemic Situation Generate Walkable Cities? by Leticia Sabino and

Louise Uchôa (SampaPé!); The Total House During and After

Coronavirus: A Virtual Place and More by Anna Rita Emili (altro_studio);

Medial Territories by Michele Cerruti But; Augmented Domesticities

- The Rise of a Non-Typological Architecture by Pedro Pitarch

One of the most important influences of the current global coronavirus pandemic

on cities might be the fact that it has made the invisible city visible: the

enormous economic inequities and unequal access to healthcare and to education,

as Beatriz Colomina points out in our conversation with her on

“Quarantines and Paranoia”. She further states that the pandemic

surely influenced our perception of cities, especially when during the lockdown

there was less traffic and the urban background became much more visible which

allowed the buildings to appear in a completely new way, beautifully and with

so much previously unnoticed details. The entire city was looking very different.

The bustle, the scene, the very vibe itself nearly vanished overnight in nearly

every city as Jessica Bridger depicts the change in her contribution

“Here Not There Urbanism”, explaining that suddenly people

could recognise all of the grocery store employees, where before city blindness

had rendered them anonymous. According to her, Covid-19 uncloaked the urban

invisible just as it put down 2-meter distance markers on sidewalks, subway

platforms, and shop-floors. Peter Dench recognised a similar effect

in central London’s red-and-white-striped hazard tape - draped across park

benches, wrapped around exercise equipment, adorning statues and forming screens

to protect bus drivers - showing the familiar in the city in a different way

in his photo-essay “Lockdown London: Tale of the Tape”. In

their article “The Great Emptiness” Carmelo Ignaccolo

and Ayan Meer point out that in the urban silence of Rome, the

only sound perceived at the Trevi Fountain was its own cascading water, arguing

that with global travel restrictions put in place to curtail the coronavirus

pandemic, tourists have become the first pandemic-induced extinct species bringing

the tourism industry to a complete halt. How cities will get on without tourism

is a question also raised by Richard Sennett during our interview

with him entitled “Isolation and Inequality”. According to

him one permanent impact of the pandemic will be economic, which will become

especially obvious in big cities. He further believes that to deal with crises

such as the current pandemic, we need to create more flexible urban environments

with decentralised nodes of concentration that can be reached within fifteen

minutes. In relation to this Alexander Jachnow reintroduces the

idea of the pocket city into the discussion, given the apparent advantages of

such a layout: small, walkable neighbourhoods are more introverted, hence less

connected and less vulnerable to the spread of disease. However, although such

possibilities of responsive planning patterns are undisputed, he considers their

implementation rather unlikely expecting little change in the creation of cities

due to the pandemic as he argues in his piece “Drivers of Change for

the “New” in the “Normal””. Nevertheless, for Joshua

Yates and Janna Hohn the Covid-19 Crisis provides an opportunity

to fundamentally change urban street-spaces as parts of a liveable, resilient

city, which has so far taken the form of temporary ad-hoc measures, but these

same measures might have the potential to develop into a form of ‘tactical

urbanism’ for long-term change, as they explain in their article “Bringing

about the Adaptive Street”. Other changes might be triggered by technology.

In her piece “The Total House during and after Coronavirus: A Virtual

Place and More” Anna Rita Emili states that the catastrophe

generated by Covid-19 has actually accelerated the globalisation of virtual

intelligence, and that in the era of the Internet the meaning of our world increasingly

requires the use of tools, platforms, and infrastructures linked to the Internet.

This phenomenon does actually lead to a transformation of social relationships

into virtual entities, but does not drag the individual towards isolation. Yet,

Sennett sees social isolation increasing - another important

effect of the pandemic. In relation to virtual spaces Pedro Pitarch

emphasises in “Augmented Domesticities: The Rise of a Non-Typological

Architecture” that while work and home have been opposite spheres in

modern life, in the contemporary city - and due to the Covid-19 Crisis - digital

technologies have generated a medium that constantly mediates between both,

establishing much more complex situations and conditions where new ‘publicness’

is achieved and performed. Living-rooms become offices, garages function as

DIY industries, bedrooms perform as TV sets, corridors as gyms, kitchens as

playgrounds, and balconies as plazas. Colomina, too, believes

that the fact that we are doing so many more things from home than previously,

which might continue after the crisis, will have huge consequences for our cities.

It may even put an end to the division between the “city of rest”

and the “city of work” which only emerged with industrialisation.

In particular - because people increasingly work from home - this will create

a significant transformation in the ways we live and might make the idea of

big office towers and the city of business obsolete, which means that we have

to think the city differently. Nonetheless, Jachnow reminds us

that cities are complex adaptive systems, capable of producing solutions to

the challenges they face and that we should be confident that through responsible

collective behaviour of individuals we will overcome not only the threats of

the pandemic, but find ways to better deal with the current distressing precautions.

And if it could be coupled, as Bridger demands, with the urgently

needed responses to the coming climate crisis - for her the crisis to end all

crises - then Covid-19 will provide more than a silver lining. It will be the

foundation for a new kind of shining, silver city upon a hill.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2020

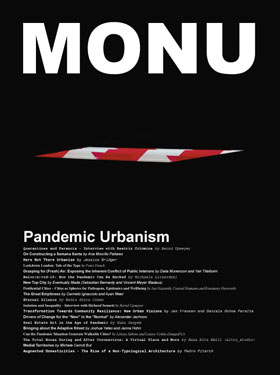

(Cover: Image is part of Peter Dench’s contribution “Lockdown

London: Tale of the Tape” on page 27. ©Peter Dench)

This

issue is supported by Lucerne

University of Applied Sciences and Arts' Master Studies in Architecture in Switzerland,

CIVA´s

Exhibition: Superstudio Migrazioni, Stroom

Den Haag’s Exhibition: Capturing Corona. The Lockdown in Photos and

Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City’s Three-month Educational Programme on

Contemporary Urbanism. Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

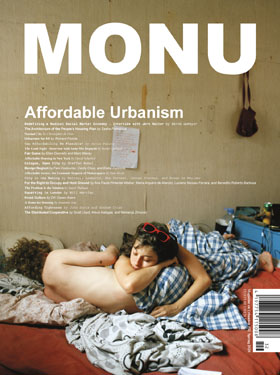

20-04-20 // MONU #32 – AFFORDABLE URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #32 here.

(browse

the entire issue #32 on Youtube)

Redefining

a Radical Social Market Economy - Interview with Jörn Walter by

Bernd Upmeyer; The Architecture of the People’s Housing

Plan by Sasha Plotnikova; Normal City by Christopher de

Vries; Urbanism for All by Richard Florida; Can Affordability

Be Flexible? by Savia Palate; The

Good Fight - Interview with Anne Mie Depuydt by

Bernd Upmeyer; Fair Game by Ellen Donnelly and Marc

Maxey; Affordable Housing in New York by David Schalliol;

Cologne, Open City by Steffan Robel; Benign Neglect by

Fani Kostourou, Cecily Chua, and Elahe Karimnia; Affordable Access: the

Economic Impacts of Makerspaces by Nate Bicak; City in

the Making by Matthias Lamberts, Ken Vervaet, Jeroen Stevens, and Bruno

De Meulder; For the Right to Occupy and Hold Ground by Ana Paula

Pimentel Walker, María Arquero de Alarcón, Luciana Nicolau Ferrara,

and Benedito Roberto Barbosa; The Problem Is the Solution by

Tanzil Shafique; Squatting in London by Will Hartley; Kiosk

Culture by DK Osseo-Asare; A Home for Housing by Jonathan

Tate; Affording Tightness by John Doyle and Graham Crist;

The Distributed Cooperative by Scott Lloyd, Alexis Kalagas, and Nemanja

Zimonjic

The creation of affordable urban spaces - whether for housing, work spaces,

public spaces, urban infrastructure, or other functions - is a complex issue,

as cost considerations must be balanced with other important objectives such

as social usability, environmental sustainability, beauty, etc. Because, as

the former Chief Planning Officer of the city of Hamburg, Jörn Walter,

argues in our interview “Redefining a Radical Social Market Economy”:

none of this is worth anything if people cannot pay for it. Following Christopher

de Vries in his contribution “Normal City”, urbanization

and gentrification have become synonymous to such an extent that they seem inescapably

paired. Global cities such as New York, Tokyo, Berlin, London, and Paris, whilst

at the centre of our collective urban imagination, appear increasingly elitist

instead of representing shared societal ideals. Although there is much evidence

that cities have predominantly been elitist over the course of history, over

the last centuries cities have transformed into beacons of civic pride, national

self-image, and stages for an increasingly inclusive democratic society, a legacy

that is under threat, according to de Vries. Thus he investigates

the ‘Normal City’ to heal our broken system, creating places not as

refuges for cosmopolitan elites, but as places of shared identity and belonging

that can represent the normal distribution of the larger urban reality. In his

piece “Urbanism for All” Richard Florida outlines

some strategies for producing a more inclusive urbanism, reflecting questions

about uneven urban development, in order to find concrete paths to improve urban

life for all, yet still believing in the value of the creative class as an engine

for economic prosperity in cities, but not as an isolated strategy. For Anne

Mie Depuydt, in our second interview entitled “The Good Fight

- Towards a Popular, Original and Productive City”, to create more

inclusive and affordable cities, municipalities need to find new ways to achieve

affordable housing, stressing the fact that people should only become the owner

of the bricks and mortar but not of the plot, meaning of the building, but not

of the land, referring to countries such as Switzerland and the UK, where such

a system exists. This provides the municipalities with advantages such as the

increase in tax revenue and an extra bargaining tool in seeking to incentivise

certain land use, as de Vries explains using the case of the Netherlands

and especially Amsterdam, where this system exists too, although currently under

threat of being scaled back or even abolished. Depuydt emphasises

further that in order to create more affordable housing, there are - apart from

the more obvious and established solution of constructing more units, the provision

of subsidies, or the implementation of rent-controls - many things architects

still need to improve, such as re-thinking our living and working spaces. To

demonstrate that affordable housing can take many forms - from cooperatives

that are collectively owned by the residents to not-for-profit developments

that rent out units at below-market rates, to public-private partnerships that

reduce the prices of single-family homes - was the idea behind David Schalliol’s

“Affordable Housing in New York” project, providing a fuller

representation of public housing in the United States and chronicling the history

of a wide variety of affordable housing models in the country’s largest

city. How diverse and vital affordable spaces for work can be, especially in

a socio-economic sense, is shown by Fani Kostourou, Cecily

Chua, and Elahe Karimnia in their article “Benign

Neglect” bringing London’s railway arches into the discussion

that are used – due to benign negligence by landowners, developers, and

the planning systems - by artists, artisans, mechanics, craftsmen, and other

businesses so they continue their productive existence within the city. These

activities present themselves as resistance to - and counter-strategy to - top-down

planning policies and neoliberal market forces resonating with a Lefebvrian

plea for rights to the city, as exemplified by the occupation movements of residual

spaces across the urban fabric of São Paulo that are brought to our attention

by Matthias Lamberts, Ken Vervaet, Jeroen

Stevens, and Bruno De Meulder in their piece “City

in the Making”. These urban movements show a valuable capacity to guide

and integrate those missing out on proper shelter. How chaotic and difficult,

but at the same time beautiful and intimate it can be when people try to claim

their right to have a roof over their head and a place to sleep at night, is

illustrated by Will Hartley in his photo-essay “Squatting

in London”. In order to make more of our city-spaces available and

affordable, Jonathan Tate reminds us - in his contribution

“A Home for Housing” - to reengage with the things that we have

left behind to the less inspirational sectors of the market, and that there

are cracks in every system and holes in every market through which design can

appear to become a generative endeavour instead of merely a decorative art,

as he shows using some vacant odd-sized lots in New Orleans that put creativity

at the start of the process. In their article “The Distributed Cooperative”

Scott Lloyd, Alexis Kalagas, and Nemanja Zimonjic

focus on ‘odd lots’ too, here in the city of Zürich, which represent

unrealized opportunities for smart densification, exploring strategies for re-imaging

a mixed-use cooperative housing development, conceived at a neighbourhood scale,

and distributed across multiple networked locations. In resisting global shifts

towards the treatment of space as an exclusive commodity in order to generate

affordable urban spaces, they intend to strengthen the community and eke out

more marginal financial gains through trade-offs, compelled by the systems of

capital that shape our cities. However, in order to produce more affordable

cities it may still be necessary to re-think capitalism, as Walter

states, but invent a radically new social market economy since all planned economy

counter-models of the 20th Century failed.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, April 2020

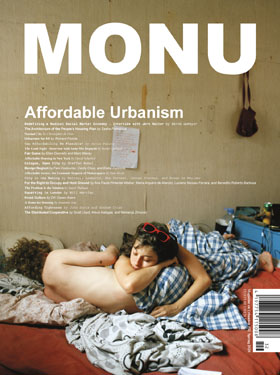

(Cover: Image is part of Will Hartley’s contribution “Squatting

in London” on page 97. ©Will Hartley)

This

issue is supported by European

Post-master in Urbanism (EMU) - Strategies and Design for Cities and Territories,

Bauhaus-University

Weimar’s International Master Course: Integrated Urban Development and

Design and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

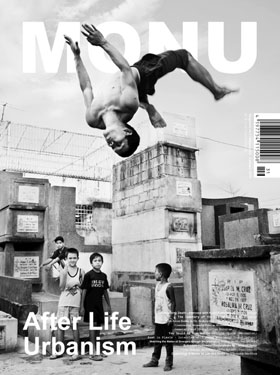

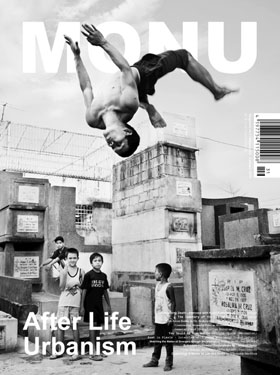

14-10-19 // MONU #31 - AFTER

LIFE URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #31 here.

(browse

the entire issue #31 on Youtube)

Democratizing

Death - Interview with Karla Rothstein by

Bernd Upmeyer; The Cemetery of the Living by Miguel Candela;

With Seven Bodies in My Backyard by Omar Kassab and Mostafa Youssef;

Constructing Memorial Poles as Monuments by David Charles Sloane;

Ghost Life Urbanism by Jérémie Dussault-Lefebvre and Sébastien

Roy; Death and Burial: In the Past Lies the Future by Carlton

Basmajian and Christopher Coutts; Beyond the Grave: Conscious Consumption

in Life and Death by Sybil Tong; Cemetery and Crematorium Futures

by Julie Rugg; The Silent City by Nicole Hanson; You

Could Be Compost by Katrina Spade (Recompose); Mourn by

Nienke Hoogvliet; Rest

in Pixels - Interview with James Norris by

Bernd Upmeyer; Watching the Wakes of Strangers through the Internet

by Andréia Martins van den Hurk; Suburban Halloween Decorations

by Cameron Jamie; Set in Stone: Humans and Barre Granite by

Monica Hutton; Claim Domain: An Urban Case for Burial by Anya

Domlesky; Exuberance and Resistance by the Dead by Bruno De Meulder

and Kelly Shannon; Coexisting: A Matter of Life and Death by Elissaveta

Marinova

To face the

urban challenges and phenomena that present themselves due to recent changes

in our society that are related to death, and its consequences for cities and

buildings, a topic that we call “After Life Urbanism”, “we

need to be simultaneously pragmatic and visionary” according to Karla

Rothstein in our interview with her entitled “Democratizing

Death”. She urges the re-engagement and coexistence with life and death

to explore what impacts all these transformations might have, encompassing first

of all spatial, but also cultural, social, environmental, technological, and

economic aspects. With his images of cemeteries of the city of Manila in the

Philippines, where families do not tread in fear of the “wrath” of

the dead but some found a place to call home among the crypts of the dead, Miguel

Candela depicts and symbolizes in his contribution “The Cemetery

of the Living” such coexistence of life and death. Omar Kassab

and Mostafa Youssef take this thought even further in their piece

“With Seven Bodies in My Backyard” arguing that the idea of the

cemetery as an apparatus of isolating death, as a form of escapism from the

reality of our own mortality, is deemed obsolete and propose to eradicate the

cemetery as a territorial land-use entirely, dispersing it throughout the city

leading to a dissolving of the cemetery. How places for mourning can be scattered

around the city is demonstrated by David Charles Sloane in his

piece “Constructing Memorial Poles as Monuments”, suggesting

to use poles, trees, and fences as “Everyday memorials” in the public

realm. That could be an innovative way to approach the problem that in the near

future many urban cemeteries will fill up, and few have room for expansion.

However, Carlton Basmajian and Christopher Coutts

see human burial, with an emphasis on natural burial instead of cremation and

the burying of embalmed bodies, as a vehicle for long-term land conservation

and restoration, and for an emotional reconnection to the eternal rhythms of

life, death, and remembrance, as they put it in their article “Death

and Burial: In the Past Lies the Future”. According to Julie

Rugg cemeteries contribute to the city a unique kind of landscape that

is highly beneficial to mental health as these are places where it is not regarded

as unusual to be solitary, and to enjoy quiet reflection, contributing emotional

intelligence to the cityscape, as she argues in “Cemetery and Crematorium

Futures”. But as long as humans continue to be buried in the ground,

whether in a beautiful and meaningful way with intentions of “placemaking”

or not, urban challenges and limitations such as the creation of affordable

housing or the construction of dense and compact cities, to name just a few,

will remain, and will require new ideas. One pioneering approach might come

from Katrina Spade and her company Recompose that

offers trailblazing burial and cremation alternatives having developed a system

that transforms a body into soil in approximately one month as a new sustainable

death-care option that has been legalized in Washington State recently, as is

explained in her contribution “You Could Be Compost”. That

technology can also introduce creativity to the discussion is revealed by James

Norris, who is the founder of the end of life planning software “MyWishes”,

in our second interview entitled “Rest in Pixels”. On MyWishes

users can plan for death, their funeral, can say their final goodbyes, and post

pre-designed content, such as updates, pictures, and comments, at defined intervals

or on certain important dates or anniversaries after their death. That information

technology, especially in the shape of the Internet, can lead to a broader cultural

shift in dealing with death and dying, contributing to the creation of both

new and alternative forms of sociability, is shown by Andréia Martins

van den Hurk in her text “Watching the Wakes of Strangers through

the Internet”. She thinks that people follow virtual wakes and live-streamed

funerals mainly out of curiosity and thus considers an interest in death, dying

and its rituals as part of human nature. Cameron Jamie documents

this interest quite clearly in his photo-essay “Suburban Halloween Decorations”,

where he depicts the elaborate Halloween decorations in his old neighbourhood

in Los Angeles. With the images that show front lawns adorned with skeletons,

witches, pumpkins, and coffins he invites the spectator into the hinterland

of death while also celebrating with a certain humour its position over that

of life through festive engagement, in which death becomes a catalyst for remembrance

of life. When dealing with “After Life Urbanism” a sense of

humour can never harm, since “it’s tough dying these days” particularly

as burials in an urban area are often very expensive, as Anya Domlesky

points it out in “Claim Domain: An Urban Case for Burial”.

Cost-cutting strategies can be found in Japan, where temples, such as Ruriko-in

Byakurenge-do in Shinjuku, feature locker-style columbariums with high-tech

vault systems for up to 7,000 urns, as explained by Elissaveta Marinova

in her article “Coexisting: A Matter of Life and Death”.

Apart from saving space the Ruriko-in Byakurenge-do temple bears additionally

multiple uses that are all quietly coexisting with one other, something that

has a tradition in Japan, where once temples were not only a place of prayer

and training, but also a school, hospital and a cultural complex of a museum,

concert hall, or library. But following Marinova, such progressive

projects can only happen if architects, city planners and policymakers alike

address the urgency together and break the taboo by design. Looking beyond the

overcrowded, segregated cemetery will mean a wholesome overhaul of our public

spaces and a complete reconsideration of the way we accommodate and remember

the dead - and as Rothstein says, “make them more part of

everyday life”.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2019

(Cover: Image is part of Miguel Candela’s contribution “The

Cemetery of the Living” on page 16. ©Miguel Candela)

This

issue is supported by University

of Luxembourg's Master in Architecture, European Urbanisation and Globalisation

and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

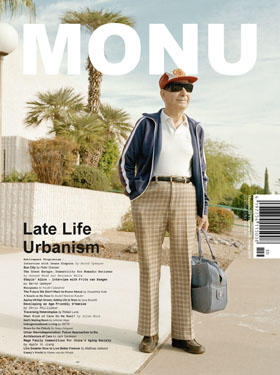

15-04-19 // MONU #30 - LATE

LIFE URBANISM

Order a

copy of MONU #30 here.

(browse

the entire issue #30 on Youtube)

Retirement

Utopianism - Interview with Deane Simpson by

Bernd Upmeyer;

Sun City by

Peter Granser;

The Great Escape: Domesticity for Nomadic Retirees by

Hannah Wood and Benjamin Wells;

Stayin'

Alive - Interview with Frits van Dongen by

Bernd Upmeyer;

Bucephalus by

Nicolò Calandrini;

The Future We Don't Want to Know About by

Anuschka Kutz;

A Knock on the Door by

Rachel Marlene Kauder;

Ageing UK High Streets: Adding Life to Years by

Luca Brunelli;

Developing an Age-friendly Urbanism by

Chris Phillipson;

Traversing Heterotopias by

Rafael Luna;

What Kind of Care Do We Want? by

Arjen Born;

God's Waiting Room by

Julienne Gage;

Intergenerational Living by

BETA;

Home for the Elderly by

Junya Ishigami;

Urban Neurodegeneration: Future Approaches to the Architecture of Care by

Jack Sardeson;

Mega Family Communities for China's Aging Society by

Apple Yi Jiang;

Live Smarter Now to Live Better Forever by

Matthias Hollwich;

Emmy's World by

Hanne van der Woude

When

debating how architecture and cities will be impacted in the future by societies

that become increasingly older due to declining fertility rates and rising life

expectancy, a topic that we call "Late Life Urbanism", we have

to consider the so-called "Young-Old", a new social group that emerged

after the mid-point of the twentieth century, as one of the driving forces of

the future, as Deane Simpson explains in an interview entitled

"Retirement Utopianism". To him this social group is so important

because the lifestyles of the people in this group - liberated from the responsibilities

of work and childcare, liberated from the responsibilities of childhood, which

involves education and socialization into society, and at the same time largely

free from rapid physical and mental decline - correspond to a shift from an

ethos of care to one of leisure and entertainment, producing new forms of architecture

and urbanism. What such new forms can look like is depicted by the photographer

Peter Granser in his photo-essay "Sun City"

that portrays one of America's oldest and largest retirement communities in

Arizona, where people are supposed to live an "active new way of life"

instead of simply hanging up the briefcase and waiting to pass away. To what

extent the growing network of young-olds are rejecting an 'aging in place',

and a sedentary and formalized retirement, in favour of a life on the move,

whether with recreational vehicles, cruise ships, or with the help of online

home-rental platforms such as Airbnb, is explained by Hannah Wood

and Benjamin Wells in their contribution "The Great Escape:

Mobile Domesticity for Nomadic Retirees", in which they describe those

retirees as pioneering and adventurous nomads. That people want to remain active

and go on for as long as possible is argued by Frits van Dongen,

the former Chief Government Architect of the Netherlands, who, after more than

thirty years of experience and being in his early 70s, just recently opened

a new office that he describes on his website as a "young Amsterdam-based

office", in another interview called "Stayin' Alive".

Of course, we all wish to live long lives, Anuschka Kutz agrees

in her piece "The Future We Don't Want to Know About". But

she points out that by creating categories such as the "Young-Old"

or the "Third Age" - a period of largely comfortable and often 'successful'

ageing - in which we are more or less fit to carry on with our lives as before

- the 'fun phase of ageing' of 'never-ending holidays' - we have automatically

generated a 'scary room' for those of high age, the "Old-Old" or the

"Fourth Age", and for those who are prematurely incapacitated or frail

and who suffer disability, bereavement, loneliness, and cognitive decline. To

prepare our cities for the old-old, to create an age-friendly urbanism and re-shape

urban society in ways that acknowledge the changes associated with ageing populations,

the gerontologist Chris Phillipson suggests a range of interventions

that he details in his article "Developing an Age-friendly Urbanism:

Re-thinking the City for an Ageing Society". He urges us to re-think

the way we both live and manage our urban environments and raises the following

questions: do older people have a 'right' to a share of urban space? How

can the resources of the city be best used to benefit the lives of older people?

Is the idea of 'age-friendly' caring communities compatible with modern urbanisation?

Furthermore, he emphasizes the importance of ensuring spatial justice for older

people as a crucial part of the debate and to develop an integrated approach

to demographic and urban change as a key task for research and public policy.

According to Rafael Luna, technology will play a crucial role

in improving the lives of older people in the future, referring to the case

of the city of Seoul in South Korea. In his piece "Traversing Heterotopias"

he points out that the future elderly will be a tech-savvy generation that,

although it is impossible to estimate the complexities of future technologies,

has already lived through the third industrial revolution of information technologies

and is advancing the fourth revolution of mass customization, and artificial

intelligence that gives rise to a cybernetic heterotopia for the elderly. Arjen

Born provides with his photos in his contribution "What Kind

of Care Do We Want?" some clues about what such a future - in which

health care robots assist in the care for the elderly - might look like. However,

the human touch and communal ways of life with a strong sense of camaraderie

will remain relevant too when it comes to "Late Life Urbanism"

as Julienne Gage argues in her article "God's Waiting

Room", in which she introduces the case of Miami Beach, where handymen

are resolving issues for old Cuban ladies, doing much more than unplugging their

toilets or cleaning their windows. This is especially true for people with illnesses

such as dementia who ideally live in an environment that is easy to distinguish,

recognize, and remember. In order to produce such an environment Junya

Ishigami, in his project "Home for the Elderly", extracted

sections from wood-frame houses that are scheduled for demolition in various

locations throughout Japan, transported them on trucks without dismantling them,

and connected these into one new architectural structure to build a facility

specifically for elderly people with dementia. That the role of design can indeed

be at the vanguard, creating the right environment and the right support, is

demonstrated by Matthias Hollwich in his piece "Live Smarter

Now to Live Better Forever". If all of this is achieved, people do

not need, despite their age, to lose their love of life and freedom and can

maintain the zest for life and creativity in old age, as Hanne van der

Woude displays beautifully in her series of photographs on "Emmy's

World".

Bernd

Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, April 2019

(Cover:

Image is part of Peter Granser’s contribution “Sun City”

on page 14. ©Peter Granser/ from the book Sun City, published by Benteli)

This

issue is supported by Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

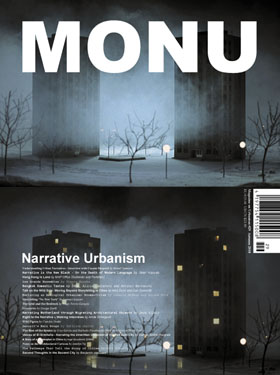

15-10-18 // MONU #29 - NARRATIVE

URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #29 here.

(browse

the entire issue #29 on Youtube)

Understanding

Urban Narratives - Interview with Cassim Shepard by

Bernd Upmeyer; Narrative is the New Black - On the Death of Modern

Language by Omar Kassab; Hong Kong Is Land by MAP Office

(Gutierrez and Portefaix); Les Grands Ensembles by Pierre Huyghe;

Bangkok Domestic Tastes by INDA, Alicia Lazzaroni and Antonio Bernacchi;

Talk on the Wild Side: Moving Beyond Storytelling in Cities by Nick Dunn

and Dan Dubowitz; Narrating an Analogical Urbanism: Rooms+Cities

by Cameron McEwan and Lorens Holm; Storytelling “No New York”

by Lorenzo Lazzari; The Grid and the Bedrock by Tiago Torres-Campos;

Geostories by Design Earth; Narrating Motherland through Migrating

Architectural Objects by Seda Yildiz; Right to the Narrative –

Walking Interviews by Amila Širbegovic; Wild Pigeon by

Carolyn Drake; Detroit’s Nain Rouge by Kathleen Gmyrek;

The Rise of the Kynics by Cruz Garcia and Nathalie Frankowski (WAI Architecture

Think Tank); Voices of El Ermitaño - Narrating the Unwritten Urbanism

of the Self-built City by Kathrin Golda-Pongratz; A Story of a

Masterplan in China by Inge Goudsmit (OMA); Notes on the Architectural

Cartoon by Amelyn Ng; The Pathways That Tell the Story of Cities

by Phil Roberts; Second Thoughts in the Second City by Benjamin

van Loon

To create a better general culture of understanding around architecture,

urban design and urban development issues, we need to use all of the narrative

tools that we have at our disposal, claims Cassim Shepard in the

interview we did with him entitled "Understanding Urban Narratives:

What Cannot be Measured" for this new issue of MONU, "Narrative

Urbanism". Being a filmmaker, he points out that moving images in this

day and age are particularly effective forms of communication as they have the

capacity to make people want to engage. For him, filmmaking is a very useful

process that taught him how to talk to people, how to listen to people, how

to observe spaces critically and with an open mind, in order to understand the

unique urban dynamics that make every space special and worthy of care. Without

that extra attention many things in our cities can simply be forgotten. With

his contribution "Les Grands Ensembles" - a video still of

a film depicting model replicas of two modernist high rise buildings in a barren

nocturnal landscape in the suburbs of Paris - the French artist Pierre

Huyghe attempts to fight such urban amnesia by representing a period

that has remained marginalized and overlooked. In order to bring forth latent

stories and revelations of places and to contribute to the poetics of future

city making through narratives that are often overlooked or excluded, Nick

Dunn and Dan Dubowitz suggest in their article "Talk

on the Wild Side: Moving Beyond Storytelling in Cities" collective

walks through lost parts of cities. In that way one important aspect of Narrative

Urbanism can be understood as the effort to make the invisible visible and

as a discourse concerning the 'common' of the community, as Lorenzo Lazzari

emphasizes in his piece "Storytelling "No New York"",

depicting narratives as complex operations, and the result of the union of several

parts, that require the consideration of diverse aspects of cities. Following

Amila Širbegovic in her contribution "Right to the

Narrative", Narrative Urbanism thus has the potential to make

on the one hand observable the stories of the unheard and the unseen, and on

the other hand to create the possibility for architects, urban designers, and

city planners to participate in - but also to question and to transform - the

conditions of urban sites into which they intervene in their future practice.

How to observe the stories of the people and involve them into creative processes,

is demonstrated by the American photographer Carolyn Drake in

her photo-essay "Wild Pigeon", for which she traveled through

the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China, around 3.000 km from Beijing,

with a box of prints, a pair of scissors, coloured pencils, and a sketchbook,

asking willing collaborators to draw on, reassemble, and use their own tools

on her photographs. And once non-experts are involved in creative processes

and the shaping of cities, the urban dynamics can change, which leads - according

to Kathleen Gmyrek - to participatory narratives, as she argues

in her piece "Detroit's Nain Rouge", in which she explains

how a myth around a red dwarf known as the Nain Rouge, that inspired a parade

in the city of Detroit, offers a public forum for participants to grapple with

the political and socioeconomic forces that are shaping the city's future, providing

the opportunity to play an active role in framing the narrative of their city.

However, since architects are great storytellers too, as Inge Goudsmit

from the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) reminds us

in her contribution "A Story of a Masterplan in China", they

will remain - together with everybody else involved in the creation of cities

- obliged to make themselves understood better, using the power of "narratives"

to help them to connect not only to experts and intellectuals in the field,

but to everybody else too. But as Cassim Shepard clarifies, such

"expert" narratives should not merely be used to get communities to

agree to new urban developments. What he believes is more important, is to try

to bring narrative strategies into the way we understand the complexity of a

site from the very beginning, and then throughout the project analyze and interpret

and develop what the project is about. For, as Benjamin van Loon

points out in his article on the city of Chicago entitled "Second Thoughts

in the Second City", only through honest storytelling can design make

a difference, because if it weren't for storytelling, would cities exist at

all?

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2018

(Cover:

Image is part of Pierre Huyghe’s contribution “Les Grands

Ensembles” on page 25. ©Marian Goodman Gallery Paris/New York)

This

issue is supported by Estonian

Academy of Arts’ MA Programme and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

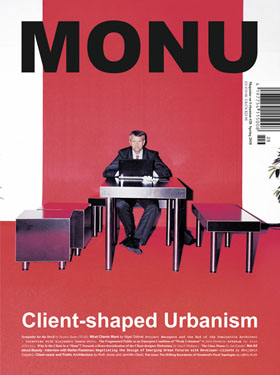

16-04-18

// MONU #28 - CLIENT-SHAPED

URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #28 here.

(browse

the entire issue #28 on Youtube)

Sympathy for the Devil by Beatriz Ramo (STAR); What Clients

Want by Nigel Ostime; The

End of the Dominatrix Architect - Interview with Alejandro Zaera-Polo by

Bernd Upmeyer and Beatriz Ramo; Expectation and Reality by

Leewardists; The Fragmented Public as an Emergent Condition of "Weak

Urbanism" by Iulia Hurducas; Arkanum by Aras Gökten;

The King As Client by Azadeh Zaferani; Arterial: The Persistence

of Flow - After the City, This (Is How We Live) by Tom Marble;

Who Is the Client in a "Slum"? Towards a Deterritorialization of the

Client-designer Dichotomy by Tanzil Shafique; Makerspaces: Public

as Client by Nate Bicak; The Clients They Are a-Changing by

Tommaso Raimondi and Paolo Romanò; Behind the Scenes: A Conversation

with my Client by Djamel Aït-Aïssa and Beatriz Ramo (STAR);

The Glass House by Jon Kandel; Not

All about Beauty - Interview with Stefan Paeleman by

Bernd Upmeyer; Negotiating the Design of Emerging Urban Futures with

Developer-clients by Benjamin Zagami; Client-users and Public

Architecture by Ruth Jones and Jennifer Davis; Architecture After

the Client by Nicholas Pajerski; Ariadne's Thread - Diverging

Trajectories of Architect, Client and User by GruppoTorto; Contested

Grounds by Nicole Lambrou; Flat Lines: The Shifting Boundaries

of Cleveland's Fiscal Topologies by Jeffrey Kruth

"Are architects at risk of losing their relevance to the client?"

asks Beatriz Ramo in her contribution "Sympathy for the

Devil" for MONU's issue #28 that we devote to the topic

of "Client-shaped Urbanism". We consider "clients"

to be crucial participants in the shaping and creating of urban spaces. We intend

to find out how to improve things, such as the collaboration between client

and architect or urban designer, for a more satisfying outcome for everybody

involved and above all for the users and inhabitants of cities. For Alejandro

Zaera-Polo architects today have not only lost the trust of clients,

but also the trust of society to deliver anything culturally significant, because

they have been fooling around with idiotic, self-involved ideas for too long

and are now viewed with some level of distrust, as he claims in our interview

entitled "Project Managers and the End of the Dominatrix Architect".

But he partly blames the clients too for this situation. On the one hand, clients

were called in, especially during the 1990s and before the financial crisis

of 2008, to do something weird and shocking that would "put the place on

the map"; on the other, they increasingly started to hand projects over

to project managers, who often took pride in belittling the architect to show

the client that they have everybody under their boot, that they are saving money,

or that they are tough with deadlines, which is, according to Zaera-Polo,

often to the project's loss. To what extent the public can be put down too,

and even excluded from city creation processes, is demonstrated by Iulia

Hurducas in her piece "The Fragmented Public as an Emergent

Condition of "Weak Urbanism"", in which she describes how

the client of every urbanism project appears as a ghostly presence, referring

to processes in the city of Cluj, Romania. Aras Gökten seems

to capture such ghostly presences in his photo-essay "Arkanum".

Money is certainly a very important aspect when it comes to "Client-shaped

Urbanism" as Tanzil Shafique emphasizes in his article

"Who Is the Client in a "Slum"? Towards a Deterritorialization

of the Client-designer Dichotomy", revealing how architects are dependent

on clients - and bound to clients - predominantly for financial reasons. Thus,

if one were to rewrite "Moneytalks", the AC/DC smash hit from the

90's, it would be called "moneybuilds". However, he points out as

well that the role of the client as the patron of 'great works of art and architecture'

is implicit and 'an a priori' in architectural practice, and that urbanism has

been shaped by clients for a long time. Nevertheless, that things can get complicated

leading easily to a tense dynamic between client and architect is dramatically

displayed in Jon Kandel's photo series about the play "The

Glass House" at the Clurman Theatre in New York City, that portrays

the particular problematic relationship between Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and

Edith Farnsworth, who became his client, acolyte, lover, collaborator, frustrated

client, spurned lover, and bitter enemy all within a few years. To avoid frustration

the Belgian real estate developer Stefan Paeleman stresses that

it is of the utmost importance that the client and the architect are on the

same team, respecting each other, and working in the same direction to achieve

a common goal, as he explains in our second interview called "Not All

about Beauty". How architects and urban designers might establish more

trust and initiate more constructive partnerships with their clients is an issue

discussed by Benjamin Zagami in his contribution "Negotiating

the Design of Emerging Urban Futures with Developer-clients": by embracing

a co-creation process, escalating the conventional client-practitioner dynamic

by enabling clients to become active participants and co-designers. According

to Ruth Jones and Jennifer Davis the future users

are ideally the clients of projects as they explain in their piece "Client-users

and Public Architecture: A Look at the Approaches of French Architect Patrick

Bouchain and the French Architectural Collective Exyzt", imagining

a collaborative engagement of the public in the creation of architecture while

making, and funding, architecture conceived as active sites for the collective

construction of citizenship. For whom this sounds too utopian Jeffrey

Kruth suggests - since the client-architect relationship has shifted

from one of patronage to a broader system of data-driven management practices

- that architects re-shape their role into one of dexterity that can consistently

be placed in a position of agency to help re-shape the environment in societally

beneficial ways, as he points out in his text "Flat Lines: The Shifting

Boundaries of Cleveland's Fiscal Topologies". That could lead to new

forms of analysis, representation and experimentation, in practice providing

agency for designers and planners, that better shape the space in which architectural

practice occurs.

Bernd Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, April 2018

This

issue is supported by Bauhaus

University Weimar’s International Master Course, Birkhäuser‘s

Vienna – Then and Now, Estonian

Academy of Arts’ MA Programme,

Sotine’s Handmade Jewellery,

Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

(Cover:

Image is courtesy of Aras Gökten. The image is part of his contribution

"Arkanum" on page 34. ©Aras Gökten)

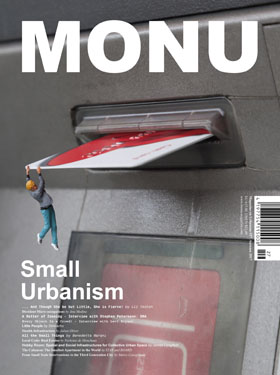

16-10-17 // MONU #27 - SMALL

URBANISM

Order a copy of MONU #27 here.

(browse

the entire issue #27 on Youtube)

... And Though She be but Little, She is Fierce! by Liz Teston; Build:

Losing their Identity by Colin Davies; Dissident Micro-occupations

by Ana Medina; Gang Urbanism: Subaltern Bodies Inhabiting Suburbia

by Victor Cano Ciborro; A

Matter of Zooming - Interview with Stephan Petermann/ OMA

by Bernd Upmeyer; Stools as Tools: Tactical Units and Ways of

Sitting in Public Space by Avsar Gürpinar and Nur Horsanali;

Every Object Is a Crowd! - Interview

with Levi Bryant by Bernd Upmeyer;

On Triangles in Squares and the Color of Air by Kyle Miller; Raptures

by Masha Hupalo; Small Scale Practice by Hester van Gent;

Little People by Slinkachu; Stealth Infrastructure by

Julian Oliver; All the Small Things by Benedetta Marani; Local

Code: Real Estates by Nicholas de Monchaux; Hobby Room: Spatial

and Social Infrastructures for Collective Urban Space by James Longfield;

The Cabanon: The Smallest Apartment in the World by STAR and BOARD;

The Apartheid that Can't Be Flushed Away by Nadine Botha; Seeding

the City in Ulaanbaatar's Ger Districts: Urbanisation from the Inside-out

by Joshua Bolchover; Small Urbanism for Refugees by Fabiano

Micocci; From Small Scale Interventions to the Third Generation City

by Marco Casagrande

"… And Though She be but Little, She is Fierce!", the

title of Liz Teston's contribution using a quote from Shakespeare's

"A Midsummer Night's Dream", captures the content of this MONU

issue on "Small Urbanism" very well. For when it comes to urbanism,

small things seem to matter, whether they are actions, small physical elements,

information and communications technology, or small-scale interventions. With

regard to actions, Teston shows how transient micro-urbanisms of protest

architecture can have a significant impact on our cities. During such actions,

human bodies can alter public spaces through practices that challenge the arrangement

of urban power and convert it into a channel of opposition, as Ana Medina

argues in her piece "Dissident Micro-occupations".

In her explorations of dissident architectural practices, she reveals that spaces

for protests are in fact not designed, but taken over by the dissidents to transform

the architectural urban landscape. However, the design of physical elements

- and especially small physical elements - appears to be very relevant for "Small

Urbanism", as architecture and urbanism seem to remain the key interface

of the physical manifestations of our society. Every architectural element,

whether big or small, seems to have an urban consequence, as Stephan Petermann

from the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) puts it in

our interview with him entitled "A Matter of Zooming". How

we design things can make a real difference in our lives, both socially and

politically, and we should be attentive to that, claims the philosopher Levi

Bryant in another interview that we titled "Every Object is

a Crowd!". According to him, objects exist, within the framework of

object-oriented ontology, at a variety of different levels of scale and all

objects are composites of other objects. Additionally, there is a gravity of

things and a power of materiality that makes all sorts of profound differences

in the world and in cities. With his miniature people, the artist Slinkachu

aims to make visible these differences that small things can make, which can

easily be overlooked and ignored. He achieves this intriguingly in his contribution

"Little People". That small but important objects in our cities

can easily go unnoticed, because they are sometimes hidden on purpose, especially

when it comes to information and communications technology and in particular

to cellular infrastructure that is necessary for mobile phone networks, is revealed

by Julian Oliver in his piece on "Stealth Infrastructure".

By exposing our cities' less visible infrastructure he aims to remind us of

our dependence on a deeper physical reality - and our consequent implicit vulnerability

- and that our cities are engineered and technical places as much as they are

natural expressions of the Human and the Social. To what extent small information

and communications technology tools and devices can be used for the renewal

of entire neighbourhoods and the fight against criminality in cities, is demonstrated

by Benedetta Marani in her article "All the Small Things".

And since information and information technology is growing rapidly, as Nicholas

de Monchaux puts it in his contribution "Local Code: Real Estates",

where he points out that information is increasingly spatial, and, more than

ever, urban in its origins and character, there is good news for the future

of our cities. It turns out that "Small Urbanism" is most powerful

when it is used as an urban renewal and redevelopment strategy, above all in

the form of small-scale interventions. How such strategies can work is shown

by James Longfield in his piece "Hobby Room: Spatial and

Social Infrastructures for Collective Urban Space", where a series

of small hobby rooms, designed for residents to pursue activities either individually

or in groups, is inconspicuously knitted into the grain of the housing, as a

new site for civic engagement and for the retention of the social ties of a

close-knit working class community. Small-scale interventions can also be used

as a design methodology on the urban fabric aiming at ripple effects and transformation

of the larger urban organism, as Marco Casagrande proposes in

his article "From Small Scale Interventions to the Third Generation

City". Through his project in the city of Taipei he demonstrates how

such interventions, while being in touch with site-specific local knowledge,

are able successfully to produce small-scale, but ecologically and socially

catalytic developments on the built human environment.

Bernd

Upmeyer, Editor-in-Chief, October 2017

This

issue is supported by University