News

Issues Interviews Order

About Follow

Support Submit

Contact ©MONU

14-06-24 // CONFLICT AS CONDITION - INTERVIEW WITH EVE BLAU

Left: Destruction: a main street in Bucha, Ukraine, photographed on March

1, 2022 during a pause in fighting.

The city, just northwest of Kyiv, was the site of fierce battles from February

27 through to the end of March. Image by Radio Free Europe

Right: Reconstruction: the same Bucha street during roadworks in May 2023. Image

by Radio Free Europe

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Eve Blau, who is a Professor of the History and Theory

of Urban Form and Design at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University.

Her research engages a range of issues in urban and architectural history and

theory, and is concerned with the complex dynamics of urban transformation in

the context of rapidly changing sociopolitical conditions. Her particular interest

in “instabilities” and “transitions” when it comes to cities

and buildings, which are both conditions that typically result from conflicts,

made us want to speak with her about “Conflict-driven Urbanism”. The

interview took place via Zoom on June 14, 2024.

Instabilities and Transitions

Bernd

Upmeyer: Without any doubt we have just entered a new era of conflict. Conflicts

are on the rise. Thus, with this new issue of MONU on “Conflict-driven

Urbanism” we aim to investigate how conflicts in the past have formed,

currently shape, and will in future influence cities and buildings, whether

these conflicts are armed or unarmed conflicts. Therefore, we are interested

in how conflicts “drive” urbanism, both in a positive and a negative

way. What were your first thoughts when we initially approached you to speak

with you about “Conflict-driven Urbanism”?

Eve Blau: I was intrigued by the question about “Conflict Urbanism”

or “Conflict-driven Urbanism” as a framework, and my first thought

was that urbanism is inherently conflict-driven. Processes of urbanization involve

a certain amount of violence and destruction. Urban planning and design are

always intervening in, and acting on, what is there. Cities are places of power,

they are places of representation, and of course, they are also places of contestation,

they are contested spaces. I think that is both positive and negative.

Accordingly, conflict is characteristic of cities because of the constant presence

of difference, of opposition, contrast, and encounter with the other. I am always

reminded of Marx’s and Engels’ famous dictum about the city; that

cities are the privileged loci of history, not only places where history is

inscribed, but where history is made. To intervene in the city is therefore

a political act with material consequences. Planning, as David Harvey argues,

is an ideological act of managing conflict. The urban spatial logic of capitalism

and the role of planning in that context is to perpetuate the existing order

and is directed toward arbitrating conflict in a pluralistic society.

These ideas resonate with my own research which is concerned with the agency

of architecture, the ways in which architecture and planning can engage political

ideas and intervene in the urban spatial organization of the city. The question

that interests me is not only how ideology is manifest in architecture, but

how architecture (which is always filled with ideology) can become political

in an active way. More particularly, I am concerned with how architecture, through

its own codes and practices, can intervene politically in the urban spatial

organization of the city.

BU: Your

parents, two Austrians, immigrated just before World War II to the US. How has

this tremendous conflict, which was World War II, influenced your life and the

way you perceive architecture and cities?

EB: That is a complex question. With no clear answer. With regard to my parents,

they left Vienna before they were adults. For them it was a place in time, shaped

by childhood memories. They gave me a certain kind of access to both the place

and time. And that access, I realized retrospectively, did have some influence

on my intellectual engagement with the dynamics of transition, conflict, political

shift, and how they shape the built environment. But the conditions that most

directly influenced how I perceive architecture and cities were the circumstances

of my own childhood. I was born in the United States, but grew up in and between

Europe and the US. My father was a historian. He was writing the classified

history of the end of World War II and the immediate post-war period, which

is why we were living in Europe. It was a project of contemporary history, directed

toward the future. Living in Germany and traveling throughout Europe I got to

know a lot about the experience of destruction, construction, and reconstruction,

as well as about the politics of space in conflict. That experience gave me

special access to those conditions and their imbricated meanings. Later, when

I was studying architectural history at Yale and writing my dissertation I acquired

a disciplinary toolkit for critically engaging with those conditions. Of course,

that toolkit is itself permanently under construction, or better said, under

reconstruction. Because the conditions I am examining are so dynamic and disparate,

the research questions that drive my research are constantly changing and I

am continuously challenged to develop new methods for analyzing and understanding

them…the complete interview was published in MONU

#37 on the topic of Conflict-driven Urbanism on October 14, 2024.

This

issue is supported by The

Complete Guide to Combat City by Julia Schulz-Dornburg; The

Berlage - MSc in Architecture and Urban Design; Royal

Academy of Art the Hague - Master’s Programme Interior Architecture (INSIDE);

The Athletic Coup - Film

Festival; and

Incognita’s Architecture

Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism. Find

out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

13-05-24 // BEAUTY CAN STILL BE FOUND - INTERVIEW WITH AI WEIWEI

View inside of one of

the six iron boxes of the S.A.C.R.E.D. installation during “Supper”

Image is courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, ©Ai Weiwei Studio

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Ai Weiwei, who is a Chinese conceptual artist, documentarian,

and activist. Many of his works are especially conflict-driven and strongly

related to architectural, urban, and spatial topics, which we at MONU considered

as particularly interesting to talk about in this issue on “Conflict-driven

Urbanism”. Several of these projects were recently exhibited in the Kunsthal

in Rotterdam under the title “In Search of Humanity”. The interview

took place in May 2024.

Life-shaping

Conflicts

Bernd

Upmeyer: With this new issue of MONU on “Conflict-driven Urbanism”

we aim to investigate how conflicts shape and influence cities and buildings,

and spaces in general, whether these conflicts are armed or unarmed conflicts.

In an interview with The Guardian in 2021 you stated that the year you were

born, your father, Ai Qing, a poet, was exiled being accused of “rightism”.

Your family was subsequently exiled to Shihezi, Xinjiang, and only returned

to Beijing in 1976 after Mao’s death. One might say that you were born

right into conflicts. How did these early conflicts shape your life?

Ai Weiwei: The conflicts that I was born into arose from the cultural cleansing

of diverse opinions and dissenting thoughts within a highly autocratic society.

These conflicts in early-stage communist countries manifested themselves in

a brutal and cruel manner. My father, a poet and politically exiled individual,

was labelled anti-party and anti-socialism. This branded us as dissenting individuals

in terms of class; the quality of our existence, all actions and thoughts, were

subjected to strict censorship and surveillance, often triggering significant

criticism. Yet, for me, this had a positive effect; it positioned me invariably

on the opposite side of mainstream culture. I was acutely aware of our difference

from mainstream culture, and even if conformity was desired, it was not permitted.

Consequently, I naturally became a rebel. I believe this has profoundly impacted

my future work, fostering a suspicion of mainstream ideologies and an innate

disdain for the masses and crowds and grandiose political ideals.

BU: In

the same interview you describe the bleakest period of this early exile as the

period when you, your brother, and your father lived in a dugout in “Little

Siberia”, part of China’s far north-west. You mention that there your

“bed” was a raised dirt platform covered with wheat stalks, with a

square hole in the roof to let in light. How was it growing up in such a place?

AW: We lived in an underground dugout, known as a “diwozi.” It featured

a small window in the roof, through which a ray of light entered. This small

detail was profoundly informative. The walls of our dugout were very thick,

matching the depth of the earth itself. That single ray of light became particularly

captivating because, without it, we would have been enveloped in complete darkness.

In such dire circumstances, I learned that beauty can still be found; it is

inherently linked to the quality of our existence. This experience brought me

a profound awareness... the complete interview was published in MONU

#37 on the topic of Conflict-driven Urbanism on October 14, 2024.

This

issue is supported by The

Complete Guide to Combat City by Julia Schulz-Dornburg; The

Berlage - MSc in Architecture and Urban Design; Royal

Academy of Art the Hague - Master’s Programme Interior Architecture (INSIDE);

The Athletic Coup - Film

Festival; and

Incognita’s Architecture

Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism. Find

out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

13-04-23

// SOCIAL BY DEFINITION - INTERVIEW WITH SHARON ZUKIN

Old social urbanism: Elizabeth Street, Manhattan

Photo by Richard Rosen

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Sharon Zukin, an American professor emerita

of sociology at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center, City University

of New York, who often writes about cities, culture, and gentrification. Her

new book, The Innovation Complex: Cities, Tech, and the New Economy, examines

the shaping of the tech ecosystem in New York. The interview took place via

Zoom on April 13, 2023.

Intriguing but Mystifying

Bernd

Upmeyer: We believe that there is a current shift in the way we use our spaces

and environment socially that involves many aspects of our contemporary social

urban life. That is why we think there is currently a unique chance and need

to rethink what the term “social” means and should mean for cities

today, whether it comes to working, living, playing, or other social urban activities

and urbanism in general.

When I first contacted you for this interview you replied that you consider

the topic of “New Social Urbanism” as intriguing but also mystifying.

What intrigues you about it and what do you consider as mystifying?

Sharon Zukin: Urbanism is inherently and by definition social. So I do not really

know what “New Social Urbanism” might mean. Maybe it means a change

of attitude, and people feel more responsible for their fellow city residents.

Or maybe it means that the elected representatives of the people are promoting

new concepts about what urbanism means. Or it could mean something entirely

different. I think what the term really suggests is spatial or “sociospatial”

change, as geographers used to say: different physical arrangements in the city,

from streets to housing to neighbourhoods, with new densities and new geographical

concentrations, that reshapes the sense of place. Since the covid-19 pandemic,

more people are thinking about these issues, from the design of public spaces

to the spatial deconcentration of leisure and reconcentration of work.

BU: You

are living since quite a long time in New York City. What are some of the issues

people are thinking about now in New York?

SZ: More than anything, at least in New York, people are dealing with the present

but looking toward the past. It is a strange moment when people are talking

about building for growth, but crises keep us anchored in the present. People

are searching for the most logical strategies for dealing with crises - the

pandemic, the housing crisis, and the ongoing crises of migration and unemployment

- that somehow will not cost too much. Thinking about New York often involves

trying to dig the city out of a very deep hole of chronic fiscal crises that

cause severe social and economic inequality. There are so many very pressing

needs that neither individuals nor the city government can pay for.

At the same time, I see many people on the streets using public space in a bigger

way than before, continuing what was happening during the pandemic. More stores,

restaurants and cafes are opening. For people like me who remained in the city

during the very dark days of the pandemic, the changes on the streets - the

liveliness, the vitality, the crush of people - all that is fantastic. Although

it was nice to have empty streets and no traffic, it was very depressing, like

living in a war zone...

…the

complete interview was published in MONU

#36 on the topic of New Social Urbanism on October 16, 2023.

This

issue is supported by The

Berlage - The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban

Design; From

‘Urban Andes’ to ‘Politics in the City’! New Architecture

& Urban Planning Books from Leuven University Press; Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City: A 12-week full-time Education Programme on

Contemporary Urbanism, Dealing with Right to the City, Climate Change and Superdiversity;

and

Incognita’s Architecture

Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism. Find

out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

16-06-23

// BETWEEN THE CITY AND THE FAMILY - INTERVIEW WITH IZASKUN CHINCHILLA

Cycle to School, gates

©Izaskun Chinchilla Architects

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Izaskun Chinchilla, who is a Spanish architect

who graduated from the Technical University of Madrid, where she has been running

her own office ‘Izaskun Chinchilla Architects’ since 2001. Currently,

she is Professor of Architectural Practice at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Her work has been exhibited at the 8th and 10th Venice Biennale of Architecture,

among other places. In her projects she proposes multidisciplinary exercises

in which, through ecology, sociology or science, architecture goes beyond stylistic

distinctions and meets again the complexity of real life in our contemporary

world. The conversation took place via Skype on June 16, 2023.

[...]

Bernd

Upmeyer: Your recent project “100 Chairs for Logroño” focuses

on public engagement and participation and relates to a certain extent to your

idea of “Urbanism of Friendship” too. What is the project about and

what role might public participation play in a “New Social Urbanisms”?

Izaskun Chinchilla: That is a project that we have been able to analyze already

more than the “Urbanism of Friendship” project. It was very important

to actually evaluate what was happening in the project in which we were distinguishing

three different topics that have been very important as social purposes.

The first was public engagement, meaning that we provide people with chairs

that are foldable, that they participate in their design, and that they need

and want to move with them around the city. Our aim was to answer the question

what the best participatory area in the city would be; what a possible area

for pedestrization would be; and to what extent the chairs were working as an

instrument for public engagement.

The second topic was related to “placemaking”. We considered that

an important aspect too, as cities are gradually becoming more similar to each

other and architecture ever more international, which makes it increasingly

difficult for people to identify with places and to have a sense of belonging

within a neighbourhood. So, with the 100 Chairs we were trying to create connections

of people with buildings, especially heritage buildings, and the local culture.

We were also proposing that the participants would look at the local features

and the local landmarks of the city.

With the third topic we were trying to evaluate how the project can promote,

and contribute to, social capital. Because in the project we were motivating

people to come together, move chairs together, create associations, and to find

places to meet, for example, to draw together on a Saturday afternoon. By doing

this we discovered that all these activities were creating social capital and

prosperity in a very objective way.

So, these were the three main objectives to actually enrol the community in

the design and in the critical use of the chairs in the city of Logroño

to increase participation and a sense of community in the city and to increase

this idea of social capital.

BU: With

your “Cycle to School” project from 2015 for the Camden Council in

London you aimed to investigate the role that children play in the urban space,

empower the urban and domestic legacy of this generation, and create social

opportunities for them. What were the main objectives and questions of this

project?

IC: When we started this project the original question concerned what we could

advise children on how to go to school between Euston Station and King’s

Cross. So, we asked ourselves at what age children were able to orient themselves

in a neighbourhood so they are able to bike alone and without risk. Obviously,

there is very traditional literature about the perception of cities. But when

we started working, using this kind of literature, like Kevin Lynch’s “The

Image of the City”, this was not very useful, because children do not perceive

cities like Lynch was portraying it. This is when public engagement came into

play to create our own knowledge. So, we organized workshops with children between

4 and 14. In two of them the children were coming alone, and in the other two

they came with their families. In the workshops we were asking them whether

they recognized actual buildings and whether they could recognize little doll

houses representing Euston Station and St Mary’s Church, the buildings

in the area. We were starting to understand when the children recognized buildings

and the reasons for it and we discovered that children who are 4 years old were

only able to distinguish and recognize certain buildings when they associate

them with very personal experiences like: “This is the place I first sang

a song in public with my aunt”. But they were not perceiving any differences

in the mass, the material, or in the colour of buildings. This empirical knowledge

that we were gathering by working with people in these workshops demonstrated

that social engagement is not just social participation. In social participation

you can ask people “what colour would you like for the top of this building”,

and then they vote pink, and they go home. But what we were doing is a bit more

complicated, because we were able to gather empirical knowledge that is obviously

not universal, including local considerations, and which I think is a solid

piece of research for other designers to use too. And families were provided

with tools that they can use for an early independence of their children by

showing them routes that are not based on street names or buildings, but identified

by animals and activities that were fun and that were happening in front of

the buildings...

…the

complete interview was published in MONU

#36 on the topic of New Social Urbanism on October 16, 2023.

This

issue is supported by The

Berlage - The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban

Design; From

‘Urban Andes’ to ‘Politics in the City’! New Architecture

& Urban Planning Books from Leuven University Press; Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City: A 12-week full-time Education Programme on

Contemporary Urbanism, Dealing with Right to the City, Climate Change and Superdiversity;

and

Incognita’s Architecture

Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism. Find

out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

22-04-22

// TO BE FINISHED IS TO BE DEAD - INTERVIEW WITH MARK WIGLEY

Mark Wigley and Brett Steele speaking about the institute of failure

in a public conversation

moderated by Enrique Walker at Columbia University GSAPP in New York, 2012

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Mark Wigley, who is Professor of Architecture

and Dean Emeritus at Columbia University. He is a historian, theorist, and critic

who explores the intersection of architecture, art, philosophy, culture, and

technology. His books include Cutting Matta-Clark: The Anarchitecture Investigation;

Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design; Constant’s New Babylon:

The Hyper-Architecture of Desire; and Derrida’s Haunt: The Architecture

of Deconstruction. He has curated exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, the

Drawing Center, Columbia University, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art,

Het Nieuwe Instituut, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture. The interview

took place via Zoom on April 22, 2022.

[...]

BU: During the early years of your career, we believe it was in the 1980s and

just after you moved from New Zealand to New York City, you founded together

with Brett Steele something that you called the “Institute of Failure”,

an institution seemingly for the instruction and theory of failure as opposed

to success. In a lecture in 2011 at the AA School of Architecture called “Architecture

of Failure” you were talking about this institute stating that success

and failure are inseparable in architecture and that failure might be an architectural

concept. To what extent would you describe “unfinishedness” of buildings

and cities as failure, as you understand it, and what would that mean for “Unfinished

Urbanism”?

Mark Wigley: I have to say that the “Institute of Failure” was a fiction.

Now you can choose whether to believe what I am about to say or not but Brett

Steele and I were both directing schools of architecture, myself in New York

and Brett in London, that were famous for their obsession with experimentation.

By definition, we were running schools that embraced failure. Then we considered

the possibility that probably there should be institutes of failure. So, at

a certain moment, when we started doing certain public conversations each year

to compare notes, we reminisced about this institute of failure that we had

supposedly constructed in New York in the 1980s that had itself failed and we

told the story of this failure in order to embrace and explain what failure

is. Getting back to your question, failure does relate to the question of the

unfinished because to be unfinished you have to have a sense of what it could

have been if it was finished. Implied in the “unfinished” is the idea

of a plan. Inasmuch as designers, architects, industrial designers, and planners

make plans they already construct the possibility of the unfinished. So, if

what I said to you before is true, that architecture is the image of something

finished, this also means that designers always live with the idea of the unfinished

and feel themselves to be in the middle of something unfinished. In education

and research, we will always be interested in the kind of life of the unfinished.

The paradox is that the architects required to produce these objects that are

supposedly finished are themselves perpetually feeling incomplete and unfinished.

And that feels like failure, which is a kind of engine driving their work.

BU: I

think for architects it is also always important to call something finished

to be able to move on with projects. Otherwise, they might be busy with their

clients forever, who would never stop requiring more things within the same

contract, which can then easily become a financial problem. Thus, the definition

of a project as “finished” might many times be a very pragmatic way

of dealing with projects.

MW: But I think it is not so bad to be unfinished, because to be finished

is to be dead. This object that represents us is finished because it is dead,

it has no future. Its future state is always the same it is now, which means

it has no future. The idea to make an object that is finished is the idea to

make something without a future, a future for itself, but also for those who

encounter it. If we imagine that architects always fail in their attempt to

finish things, you can at least say that they and their projects are alive.

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#35 on the topic of Unfinished Urbanism on October 17, 2022.

This

issue is supported by The

Berlage - The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban

Design; Estonian

Academy of Arts (EKA): Urban Studies MSc; KU

Leuven’s Master of Human Settlements and Master of Urbanism, Landscape

and Planning; Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City:

Dirty Old Town; Learning From Rotterdam - A Unique 12-week Post Graduate Education

Programme; and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

10-06-22

// UNFINISHEDNESS, A PRACTICE - INTERVIEW WITH BPLUS.XYZ (ARNO BRANDLHUBER

AND OLAF GRAWERT)

Street facade of Brunnenstraße 9, Berlin

Photo ©Erica Overmeer

Bernd Upmeyer spoke to bplus.xyz (Arno Brandlhuber and Olaf Grawert) about “Unfinished

Urbanism”. Arno Brandlhuber is a German architect and university professor.

In 2006, he founded the Berlin-based office Brandlhuber+, which is currently

reforming with a new structure in an equal partnership as bplus.xyz. bplus.xyz

understands itself as a collaborative architecture practice that brings together

different actors from theory to practice with different formats from buildings

to campaigns, exhibitions, texts and films. Olaf Grawert is an Austrian architect

and author, and partner at bplus.xyz. The interview took place via Zoom on June

10 and 24, 2022.

”Unfinished” Berlin

Bernd

Upmeyer: Your work has only rarely been characterised, whether by you or by

others, as “unfinished”. However, we have the impression that some

of your ideas for Berlin, many of your projects, and especially your research

on political aspects of our built environment, are strongly related to our topic

of “Unfinished Urbanism”. In Berlin, your project Brunnenstraße

9 in particular, has been described in 2009 by the German architecture magazine

Bauwelt as a building where the “unfinished” is program. Do you agree

with that description?

Arno Brandlhuber: Our architecture practice is actually unfinished by itself.

Let’s say it is a collaborative practice since always. It is never finished

in terms of “who is the student, who is the actor, who is having agency”.

But this unfinishedness is related to finishedness too, as we still think that

we could finish and improve the world. But we no longer regard architecture

as an object that is finished at a certain moment. We see architecture as a

process of cutting and taking care of it over the lifespan of a building. And

for sure legal matters are a huge part in our practice.

BU: The

“+” symbol that you added since always to the name of your offices

seems to represent that kind of “unfinishedness” in your work.

AB: Additionally to “+” we added “xyz”, which is not only

the ending of the alphabet or the name of a domain, but it also represents our

unfinishedness as a practice to a certain extent. But to come back to your question

for the Brunnenstraße project, I would agree with the description of the

project as unfinished even if Bauwelt still focuses too much on discussing objects.

They usually discuss finished projects. But then they discovered that this project

seems unfinished and that it cannot be described differently than as unfinished.

There are actually two ways I would describe it as unfinished. One relates to

the fight against the “critical reconstruction” of Berlin, framed

by Hans Stimmann, the Senate Building Director of Berlin at that time. Although

the Brunnenstraße project related to the height of the neighbouring buildings,

its image did not. Its image was to be an open building. With its unfinishedness

it reacted to the very finished image of the “stony” Berlin idea that

Stimmann tried to create or recreate. The second unfinishedness of the Brunnenstraße

project is related to the use of the building. Our aim at that time was to study

how cheaply one could build it and how minimally one could interpret the required

regulations so that you are able to work, live, and party there. As we wanted

to move our office into this building too, we asked ourselves what we really

needed. You need soft light, you need some heating, but you do not need certain

requirements that might be written down somewhere and that are related to a

notion of finishedness. At that time, it was as much finished as necessary to

be used, to be accessed. You cannot imagine it today, but the building did cost

1000 Euros per square meter, the entire construction.

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#35 on the topic of Unfinished Urbanism on October 17, 2022.

This

issue is supported by The

Berlage - The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban

Design; Estonian

Academy of Arts (EKA): Urban Studies MSc; KU

Leuven’s Master of Human Settlements and Master of Urbanism, Landscape

and Planning; Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City:

Dirty Old Town; Learning From Rotterdam - A Unique 12-week Post Graduate Education

Programme; and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

24-06-21

// THE MAGIC OF SQUATTING - INTERVIEW WITH HANS PRUIJT

Metropoliz Squat, Rome, 2014.

Photo by Hans Pruijt

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Hans Pruijt, who is an assistant professor

at the Sociology Department of Erasmus University in Rotterdam. His main topic

of interest is empowerment in various contexts, especially working life and

urban social movements. In the late 1970s he was involved in the Dutch squatting

movement occupying buildings to fight against the demolition of entire neighbourhoods

in Amsterdam. As a sociologist he has written extensively on the topic of squatting

in articles such as “The Impact of Citizens’ Protest on City Planning

in Amsterdam”, “Squatters in the Creative City”, or “The

Logic of Urban Squatting”. The interview took place via Zoom on June 24,

2021.

[...]

Bernd Upmeyer: In 2004 you wrote a piece called “The Impact

of Citizens’ Protest on City Planning in Amsterdam”. What did you

argue?

Hans Pruijt: The main arguments of the article I had written down already in

1984, because they were part of my master thesis. But in 2004 I got the chance

to publish some of the ideas. In the article I described what city planning

looked like in 1968 when planners wanted to get rid of many 19th Century neighbourhoods

and create a subway network, making bigger roads, and a central business district.

I traced all these plans and showed what would have happened to them without

the protests. Eventually most of them got derailed, because of the protest movements

in which many squatters were involved that I described earlier. And in the article

I described how the protests made the projected central business district in

the Eastern part of the inner city less feasible, especially since a viable

alternative location in the south was available. This location, now named the

“Zuidas” 10, was eventually developed. I based my prediction on studies

researching what businesses really need and want. Because what they especially

wish for is to have good access to roads so they can easily be reached by car.

And since the plans for larger roads in the centre of Amsterdam were thwarted

and sabotaged by the protests that were squatting and blocking highway plans,

Amsterdam’s inner city was therefore no longer attractive to larger businesses.

But as building larger roads was still possible in the south of the city, Amsterdam’s

city planning was changed accordingly, which demonstrates the impact of protests

on city planning.

BU: In

2011 and in “The Logic of Urban Squatting” you explain that squatters’

movements can overlap with other urban movements in protest waves. How does

that work and how powerful are such amplified protests waves?

HP: Social movements typically occur in waves and one of these waves occurred

around 1980. That happens when at the same time in different locations and different

countries protests take place on different topics that are somehow interconnected

and inspire each other. One of the recent protest waves is the Arab Spring.

Populism, whether left-wing or progressive, I would describe also as a protest

wave. And squatting was especially important in the protest waves of the 1980s

and also important in the protest wave of 2011 in Southern Europe, the 15-M

Movement, when a lot of young people were unemployed and had no future, who

then organised big occupations and protests. There are always enough reasons

to protest, like the fact that today it is almost impossible for young people

to find an affordable place to live here in The Netherlands, where we have an

enormous housing shortage.

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#34 on the topic of Protest Urbanism on October 18, 2021.

This

issue is supported by

Material District´s

Book: Tomorrow’s Timber, Lucerne

University of Applied Sciences And Arts: Master Studies in Architecture in Switzerland,

Estonian

Academy of Arts (Eka): Urban Studies MSc, Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City:

Dirty Old Town; Act Now! - A Unique 12-week Post Graduate Education Programme,

and University

of Basel: Master of Arts - Critical Urbanisms. Find out more about MONU's

supporters in Support.

17-05-21

// LEARNING FROM PROTESTS - INTERVIEW WITH MABEL O. WILSON

Mario Gooden’s protest machine at the “Reconstructions: Architecture

and Blackness in America” exhibition, MoMA, New York

Photo by Robert Gerhardt

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Mabel O. Wilson, who is the Nancy and George

Rupp Professor of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, a Professor in African

American and African Diaspora Studies, and the Director of the Institute for

Research in African American Studies (IRAAS) at Columbia University. Through

her transdisciplinary practice Studio&, Wilson makes visible and legible

the ways in which anti-black racism shapes the built environment and how blackness

creates spaces of imagination, refusal, and desire. Her research investigates

space, politics, and cultural memory in black America; race and modern architecture;

and visual culture in contemporary art, media, and film. Wilson co-organized

with Sean Anderson the exhibition ‘Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness

in America’ at The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA). The conversation

took place via Zoom on May 17, 2021.

Manifestations, Methods, and Strategies of Today’s Protests

Bernd

Upmeyer: While urban protests featured in both of our last two MONU issues -

in #32 on more affordable cities and in #33 on the consequences of the coronavirus

pandemic for cities - but merely as a side topic, with this new issue of MONU

we would like to focus entirely on protests as an urban phenomenon, as they

appear frequently and intensely as an urban approach for change these days.

In a time when most activism is expected to take place in the digital realm

and via social media - not only because of the coronavirus pandemic - such numerous

mass-events in the physical spaces of our cities might come as a surprise, which

intrigued us to such an extent that we decided to study them further. Why do

you think mass-events and mass-protests are happening still today in the physical

spaces of our cities and not merely in the digital realm?

Mabel O. Wilson: Social media monetised social relations. What used to be for

the most part free social behaviour—conversation and friendship between

individuals—is now mediated, monitored, and monetised by private transnational

corporations like Facebook and Twitter. Thus how individuals and groups organise

protests is still a vital public activity, even though the social media age

marks a shift in form and forum. I would also argue that there is still some

necessity and validity in having physical bodies in a public space, feet on

the ground so to speak, in order for a protest to have an effect. And given

recent protests around the world from Minneapolis to Hong Kong that fact does

not seem to have changed. Bodies occupying large spaces or marching through

different types of arteries - be it streets or freeways - still seems to be

a central tactic for how people engage in forms of political protest.

BU: The

reasons for recent social counter-movements all over the world have been well-documented,

discussed extensively and are mostly related to fairer distribution of wealth

and affordable housing, commercial, social and cultural spaces, and transport

costs. But the current global Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality

and racially motivated violence against black people make clear that the challenges

at stake are even bigger. What distinguishes - according to you - the Black

Lives Matter protests from other current protest movements in terms of their

motivation?

MOW: All protests have their different origins and are created within different

contexts of political power, diverse histories of nationalism, colonialism,

and imperialism. All protests also have different agendas and aspirations. With

that in mind I do not think that the current protests have a lot to do with

what happened on Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring protest, and neither with

Occupy. So I don’t think that they can be placed under the same umbrella,

but each draws its motivations from its own histories and struggles and each

of these histories has its own complexities. But there are through-lines that

forge connections such as the fight against predatory corporate power and the

violence enacted by the police and military, for example. When you look at the

current Black Lives Matter protests, you can find traces that go back to the

1960s Civil Rights and Black Nationalist struggles against anti-black racism.

But they are also related to post-colonial struggles after WWII to throw off

colonial domination and exploitation. Today’s protests emerge from the

histories of places where they occur. On the other hand one could also make

the case that Black Lives Matter is very different from the civil rights movement

because it is a different set of individuals and institutions that are leading

the charge. BLM also fights against different articulations of white supremacy

and police violence than the civil rights movement fought against. Today the

deleterious effects forged by Jim Crow1 segregation on Black lives has morphed

into new regimes of exploitation and de-humanisation such as mass incarceration.

Since its inception in response to the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012 BLM

has been remarkable in terms of how it has been able to sustain both its message

and its impact as a protest movement.

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#34 on the topic of Protest Urbanism on October 18, 2021.

This

issue is supported by

Material District´s

Book: Tomorrow’s Timber, Lucerne

University of Applied Sciences And Arts: Master Studies in Architecture in Switzerland,

Estonian

Academy of Arts (Eka): Urban Studies MSc, Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City:

Dirty Old Town; Act Now! - A Unique 12-week Post Graduate Education Programme,

and University

of Basel: Master of Arts - Critical Urbanisms. Find out more about MONU's

supporters in Support.

24-08-20

// ISOLATION AND INEQUALITY - INTERVIEW WITH RICHARD SENNETT

“What I discovered was that neighbourhoods

became socially more connected and more

short distance social networks were established.”

(Richard Sennett)

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Richard Sennett, who currently serves as Senior

Advisor to the United Nations on its Program on Climate Change and Cities. He

is Senior Fellow at the Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University

and Visiting Professor of Urban Studies at MIT. Previously, he founded the New

York Institute for the Humanities, taught at New York University and at the

London School of Economics, and served as President of the American Council

on Work. Over the course of the last five decades, he has written about social

life in cities, changes in labour, and social theory. His books include The

Hidden Injuries of Class, The Fall of Public Man, The Corrosion of Character,

The Culture of the New Capitalism, The Craftsman, and Building and Dwelling.

The conversation took place via Skype on August 24, 2020.

[...]

Bernd Upmeyer: Do you think that the pandemic will have an impact on the growth

and the expansion of cities, especially big cities?

Richard Sennett: The big cities will not stop growing, but – like the “15-minute

cities” – they should disaggregate concentration in order that several

parts with five or six thousand inhabitants will be generated that make up the

city together. This will not only help to deal better with the pandemic, but

such a disaggregation of concentration, energies, pollution, etc. will help

to battle climate change too.

BU: As

an outlook on the future, where do you see – although many effects might

remain temporary – permanent impacts of the pandemic on cities?

RS: Well, one permanent impact is economic, which becomes especially obvious

in big cities, where there is such massive economic value. Another important

thing related to covid-19 is the creation of inequality, especially between

the working class and the middle class, as not everybody is able to work from

home, but the middle class has more possibilities there and is thus less impacted.

However, working from home has its own challenges too, since it is not possible

to manage all tasks via Zoom. Online university classrooms have their limits,

for example. But the coronavirus has really sped up our ways of working with

technology, because it became necessary for banks, insurance companies, and

many companies from the service and financial sector to figure out and decide

what can be done effectively on a computer and with online communication tools.

Because the tasks that can be done at home and in isolation have their limits

and work best when they are just routine tasks. This is something that is happening

today. I have a couple of students that are studying this and they figured out

that the first people who are going back to their actual physical offices in

London are those working in law corporations, because they need the interaction.

So, I think that the long-term effects of the pandemic are not so much related

to the number of people who died, but to the increase in social isolation and

an increase in inequality.

…the

complete interview was published in MONU

#33 on the topic of Pandemic Urbanism on October 19, 2020.

This

issue is supported by Lucerne

University of Applied Sciences and Arts' Master Studies in Architecture in Switzerland,

CIVA´s

Exhibition: Superstudio Migrazioni, Stroom

Den Haag’s Exhibition: Capturing Corona. The Lockdown in Photos and

Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City’s Three-month Educational Programme on

Contemporary Urbanism. Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

21-08-20 // QUARANTINES AND PARANOIA - INTERVIEW WITH BEATRIZ COLOMINA

“Beds were all over the news and became, in my opinion, the face

of this pandemic.” (Beatriz Colomina)

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Beatriz Colomina, an internationally renowned

architectural historian and theorist who has written extensively on questions

of architecture, art, technology, sexuality, and media. She is Founding Director

of the interdisciplinary Media and Modernity Program at Princeton University,

and the Howard Crosby Butler Professor of Architectural History in the School

of Architecture. Her work has been published in more than 25 languages and her

books include: Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Lars Müller,

2016) with Mark Wigley, The Century of the Bed (Verlag für Moderne Kunst,

2015), Domesticity at War (MIT, 2006), Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture

as Mass Media (MIT Press, 1994), and Sexuality and Space (Princeton Architectural

Press, 1992). Her new book X-Ray Architecture was released in 2019, only a few

months before the global coronavirus pandemic started. The conversation took

place via WhatsApp on August 21, 2020.

[...]

Bernd Upmeyer: If the current pandemic is not a “house problem”, but

a “city problem”, its influence might not be that big on architecture,

but rather on everything outside in the city: the urban infrastructure, the

public spaces, the road design, etc.

Beatriz Colomina: Well, the thing is that a lot of people are reorganizing their

houses, so they can work better from home. But the cities are also changing

and providing more public space and more outside spaces for restaurants, more

bike lanes, at least this is what is happening at the moment. But I think that

the most important influence of covid-19 is that it has made the invisible city

visible: the enormous economic inequities and unequal access to health care

and to education. This is, I think, the biggest effect that the coronavirus

pandemic has on the city. This is interesting also historically, because all

the former pandemics and health crises had this effect of making visible what

was already there. In this sense, Covid-19 and the Black Lives Matter protests,

which began in late May in response to the killing of George Floyd cannot be

separated, but belong together.

BU: In

that way the pandemic changed clearly our perception of things, which is a bit

related to what you said before, when you described that when in New York the

traffic was less, the backgrounds became much more visible.

BC: Yes, and all the birds became so present. In the middle of New York without

traffic or noise, without construction work, we woke up to the songs of birds.

I didn’t realize there were so many birds in New York. Or perhaps there

were not. They came when all the noise stopped and so many people fled. I read

that in other cities other crazy things happened, like wildlife walking around

the streets and recovering their territory, which, I think, is a good thing...

…the

complete interview was published in MONU

#33 on the topic of Pandemic Urbanism on October 19, 2020.

This

issue is supported by Lucerne

University of Applied Sciences and Arts' Master Studies in Architecture in Switzerland,

CIVA´s

Exhibition: Superstudio Migrazioni, Stroom

Den Haag’s Exhibition: Capturing Corona. The Lockdown in Photos and

Rotterdam’s

Independent School for the City’s Three-month Educational Programme on

Contemporary Urbanism. Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

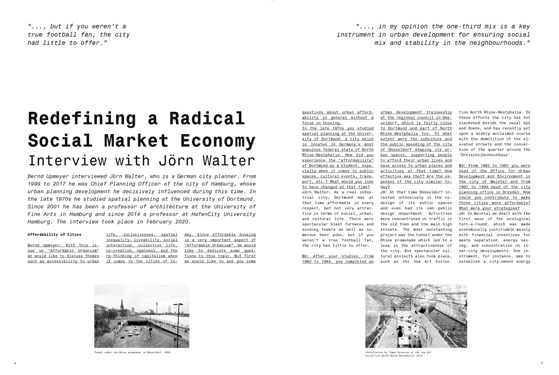

27-02-20

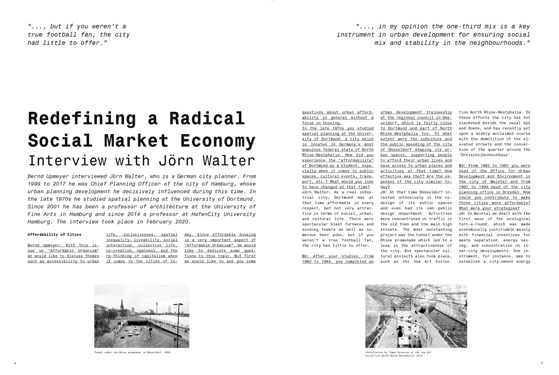

// REDEFINING A RADICAL SOCIAL MARKET ECONOMY - INTERVIEW WITH JÖRN

WALTER

Redefining a Radical Social Market Economy - Interview with Jörn

Walter, p. 4-5

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Jörn Walter, who is a German city planner.

From 1999 to 2017 he was Chief Planning Officer of the city of Hamburg, whose

urban planning development he decisively influenced during this time. In the

late 1970s he studied spatial planning at the University of Dortmund. Since

2001 he has been a professor of architecture at the University of Fine Arts

in Hamburg and since 2014 a professor at HafenCity University Hamburg. The interview

took place in February 2020.

[...]

BU: Recent and current protests around the world addressing economic justice,

such as the French yellow-vest movement that was motivated by rising fuel prices

and the high cost of living, or the current Chilean protests against rising

fares on public transit that triggered the biggest demonstration the country

has ever seen, are proof of the urgency of finding new and innovative solutions

to produce more “Affordable Urbanism”. Do you think that we have to

re-think capitalism when it comes to the cities of today?

JW: Fact is that since the liberalisation and globalisation of markets in

the 1980s, there has been a growing gap between rich and poor worldwide. Since

the 2009 financial crisis, the redistribution of wealth has not only affected

the capital, financial, and industrial markets, but also massively captured

the real estate markets, which has been mirrored in rapid increases in land

prices and rents. This is the reason for the social counter-movements all over

the world, which relate to affordable living conditions, fairer distribution

of wealth and, with the “Recht auf Stadt” movement, also to affordable

housing, commercial, social and cultural space and transport costs. In other

words, an affordable city. Since all planned economy counter-models failed in

the 20th century, we should recall those of a radical social market economy,

which were very successful in the USA since the New Deal in the 1930s and in

Europe since the post-war period with the welfare state models up to the 1970s.

At its core, the state has ensured a more equitable distribution of income and

wealth through a variety of interventions, taxes and subsidies, resulting in

a socially much more balanced and affordable supply situation. This is still

necessary and overdue today.

BU: Many

countries, especially in the Western World, are trying increasingly to make

their cities more environmentally sustainable, which is certainly a great thing.

However, more environmentally sustainable buildings or neighbourhoods are usually

more expensive to build than less sustainable ones, which might challenge therefore

the creation of more affordable cities in the future. How do you see that?

JW: This is certainly a conflict of objectives that - among others - cannot

be ignored. It does not make the specific objectives wrong, but it is clear

that optimization is only possible in the sense of a comprehensive sustainability

concept that takes ecological objectives just as seriously as social and economic

ones. In this respect, some ambitious building-related energy targets are questionable

from an economic and social point of view in terms of investment and operating

costs. In order to achieve more compatible solutions, the focus nowadays is,

for example, rightly directed away from the building to the neighbourhood. The

decisive question is always: with which measures do we achieve the greatest

effects in terms of a comprehensive sustainability concept...

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#32 on the topic of Affordable Urbanism on April 20, 2020.

This

issue is supported by European

Post-master in Urbanism (EMU) - Strategies and Design for Cities and Territories,

Bauhaus-University

Weimar’s International Master Course: Integrated Urban Development and

Design and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

21-02-20 // THE GOOD FIGHT - INTERVIEW WITH ANNE MIE DEPUYDT

“Urban software” at the Solilab & Karting Hangars in Nantes

Image credit: Samoa

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Anne Mie Depuydt, who is a Belgian-born architect

and urban planner and the director of the Paris-based office uapS that she founded

with Erik Van Daele in 1999. Before opening uapS, Depuydt collaborated with

Dominique Perrault between 1988 and 1992 and was project leader at Rem Koolhaas’

Office for Metropolitan Architecture during its pioneering early years between

1992 and 1995, working on the legendary Jussieu Library project in Paris. The

conversation took place via telephone on February 21, 2020.

Affordability and Its Limits

Bernd

Upmeyer: We got to know about you through a member of our editorial board, who

suggested you for the topic of “affordability”, describing you as

a ‘total fighter’ keeping developers in check and forcing them to

make commitments. What commitments would they need to make to create affordable

cities?

Anne Mie Depuydt: If you want to achieve an affordable city, the municipality

has to require from developers that they prevent the selling prices of the houses

from going higher than the average. It has to determine the price of a property

and the developer has to find out how he can propose a reasonable cost-price

for the building. But the problem is that if the prices of houses are limited,

very often the building cost becomes too low which makes it very difficult for

the architect to propose a good quality project. This is actually the problem

we have, for example, in Ivry, a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the

southeastern suburbs of Paris, and we know that it exists somehow everywhere

in France. Just because today the construction price in France is more or less

20% higher than two years ago. There are actually so many projects going on

in the Grand Paris and with the Olympic Games, that it leads to higher cost

prices. We are currently working on the Olympic Village, and we are confronted

with the fact that the costs of construction are 20 - 30% higher than the normal

price. This makes it very difficult for us to build qualitatively good housing

projects. And since the building costs - but also land costs - are that high,

this impacts immediately on the prices to buy houses too, which are getting

higher and higher. So, if you want affordable urbanism, or if you want to fight

so that selling prices for houses do not exceed an average of 4,500 euro per

square meter, you have a problem, because the developers are having trouble

developing projects for that price, which means for a lot of projects that they

are not possible and stop. This is happening to some of our other current projects

too. That means that cities and their municipalities need to find other ways

to achieve affordable houses. They are considering the idea that people should

only become the owner of the bricks and mortar but not of the plot.

BU: Do

you mean that people become the owner of everything that is build on a lot,

but not of the land itself?

AMD: In France, but even in Belgium, discussions are going on if one can become

the owner of the building but not of the land, like in Switzerland or London:

emphyteutic lease. There you can be the owner of a building for 30 years, 60

years, or 100 years, but you are not the owner of the land or plot. Currently,

such a system is being discussed in Paris too and might be applied in several

places. Especially in Ivry, which has historically demonstrated strong electoral

support for the French Communist Party, this has been discussed, – especially

for social housing. With this system a family can own a house for a long time,

but if the owner dies and their children are earning more than a fixed income,

they are not allowed to keep it...

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#32 on the topic of Affordable Urbanism on April 20, 2020.

This

issue is supported by European

Post-master in Urbanism (EMU) - Strategies and Design for Cities and Territories,

Bauhaus-University

Weimar’s International Master Course: Integrated Urban Development and

Design and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

27-08-19

// DEMOCRATIZING DEATH - INTERVIEW WITH KARLA ROTHSTEIN

‘Dialogue on Death’ videos at the exhibition

‘DeathLAB:

Democratizing Death’

Photo by Karla Rothstein

Bernd Upmeyer interviewed Karla Rothstein, who is an architect, professor,

and creative thinker living, practicing, and teaching in New York City. In both

her professional work as design director at LATENT Productions and through over

a decade of studios taught at the Graduate School of Architecture Planning and

Preservation at Columbia University, Karla engages with alternative and emerging

methods of corpse disposal in progressive proposals of civic sanctuary and temporal

urban remembrance. The interview took place in August 2019.

Changes

in our Society Related to Death

Bernd

Upmeyer: Ever since 2013 you have been directing the so-called “DeathLAB”

that you founded at the Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation

at Columbia University and since 2011 you have been a member of the Columbia

University Seminar on Death. What were your motivations as an architect to start

working and researching on topics of mortality to begin with? How did you become

so interested in death?

Karla Rothstein: My interest in spaces of death and remembrance emerged out

of my attention to the future of the city. Starting over a decade before the

dates that you reference, I taught complementary design studios at Columbia’s

GSAPP – in the Fall, several studios study the same theoretical New York

City site for its potential to host multifamily housing. In the Spring, I would

select both a site and a public programme for my students to engage with. I

was attracted to peripheral territories, the edges and margins of NYC, where

behaviours were somewhat less regulated and the potential for transformation

was fertile. In that context, I encountered NYC’s vast network of existing

cemetery spaces, which in aggregate occupy an area over five times the size

of Central Park. It quickly became evident that the American expectation of

a cemetery plot in perpetuity for each individual was at odds with both the

density and spatial limits of urbanity. I also found the historic positioning

and re-positioning of the cemetery compelling – going from embedded urban

churchyards to exurban sites that over time the city has surrounded. Despite

the current adjacencies, most cemeteries remain largely segregated from everyday

life.

Initially,

we accepted cremation as the solution to spatial constraints and focused on

reincorporating spaces of reflection and remembrance into a more quotidian urban

experience. But the practice of consuming fossil fuel to combust a corpse composed

largely of water also felt misaligned with contemporary priorities, and so we

began researching alternative disposition options, of which there were very

few. DeathLAB grew out of both my GSAPP design studios and the work that we

were doing in parallel in my architecture practice. The complexities of these

issues extend beyond design, and the need to involve multiple disciplines became

obvious, so we began engaging colleagues from across Columbia in dialogue on

the topic. I launched DeathLAB with associates from Earth and Environmental

Engineering, Philosophy/Theology, and the social sciences.

[...]

BU: Today

we are witnessing many changes in our society that are related to death. Which

are the most important changes in your view?

KR: Relative to twenty years ago, the degree of interest and willingness to

engage in the topics of death and disposition is truly remarkable. In the U.S.

and around the globe, populations are living longer. As the past issue of MONU

conveyed, the numbers and differentiation among the middle aged and elderly

are increasing. This reality, together with the post-WWII increase in childbirth,

means that in the U.S. alone there will be about one million more deaths in

2035 than in 2015. At that time, 78 million people will be over age 65, making

it the first time in U.S. history that this cohort will outnumber those under

age 18. The sheer number of corpses, especially in urban areas, will require

thoughtful planning.

Diversity

of belief structures and expanding interpretations of spirituality are also

relevant. Ritual practices and a sense of community are important scaffolds

during milestone events and life’s transitions, but dogmatic structures

no longer resonate with many people’s values and priorities. This dissonance

opens up space where new practices and processes are welcome and can develop

in dialogue with contemporary needs and principles...

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#31 on the topic of After Life Urbanism on October 14, 2019.

This

issue is supported by University

of Luxembourg's Master in Architecture, European Urbanisation and Globalisation

and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

03-07-19 // REST IN PIXELS - INTERVIEW WITH JAMES NORRIS

Bob Monkhouse’s television campaign for the Prostate Cancer Research

Foundation

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with James Norris, who is the founder of MyWishes.

This is a free service and one of its features allows users to post predesigned

content, such as updates, pictures, and comments, at defined intervals or on

certain important dates or anniversaries after their death. Norris is also the

founder of The Digital Legacy Association, runs an annual, international conference

called the Digital Legacy Conference and is a part-time lecturer and mentor

in digital & social media at University College London (UCL). The conversation

took place via Skype on July 3, 2019.

Posting from Death

Bernd

Upmeyer: In a 2015 interview with the BBC you mentioned that your father died

when you were quite young. Was this the moment you became interested in the

“After Life”?

James Norris: I lost my father at a time when music was very important to me.

I was going through a stage, where until just before his death, I was listening

to Jason Donovan, Kylie Minogue. I then moved onto Guns N’ Roses whose

lyrics spoke about death and imagery of skulls. My musical repertoire had a

lot of connotations about death and dying. I think that listening to words that

related to death at a time when my father was ill was very impactful. After

my Dad’s death I thought about the importance of the songs that I would

want to have played at my funeral. I think losing my father at that time created

a strong link for me between death and music.

A few years

later I came across a charity TV commercial by Bob Monkhouse, where he encourages

people to get tested for prostate cancer. What made the video so powerful was

the fact it was shot to be broadcasted four years after his death. I thought,

if a comedian could pass down his words of wisdom using a TV commercial, now,

with the internet and social media, we should all be able to say goodbye in

our own way. This led to the development of DeadSocial. DeadSocial lets users

create a series of goodbye messages. These were saved and sent out to the users

social media accounts such as Twitter, Facebook, Google+, etc. after they had

died. Users would first write their ‘goodbye message’. Once created

they assigned at least one trusted contact. They view or edit the message, but

have to authenticate the user’s death by inserting a unique code paired

with their email address.

This allowed

for pre-recorded messages to be sent after the users death at a time when the

trusted contact felt it was right to do so.

BU: You

founded “DeadSocial” in 2013. Does it still work today as it worked

at the beginning?

JN: Today “DeadSocial” has evolved into a much more comprehensive

software called “MyWishes”. It is still free to use and as well as

featuring the goodbye tool it also includes other areas like funeral planning,

bucket list sharing, and documenting your wider and online wishes in a digital

will.

If you have,

for example, a Facebook, Instagram, Gambling account, Xbox or PlayStation account,

you can make plans for each of them. This digital will can be downloaded and

emailed to someone you trust...

…the complete interview was published in MONU

#31 on the topic of After Life Urbanism on October 14, 2019.

This

issue is supported by University

of Luxembourg's Master in Architecture, European Urbanisation and Globalisation

and Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

18-02-19

// RETIREMENT UTOPIANISM - INTERVIEW WITH DEANE SIMPSON

The “Fountain of Youth” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1546

Bernd Upmeyer talked to Deane Simpson, who is an architect, urbanist

and educator teaching and researching at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts,

School of Architecture, Copenhagen, where he is professor and co-leader with

Charles Bessard of the masters program Urbanism and Societal Change. Simpson

received his doctorate from the ETH Zürich, masters degree in architecture

from Columbia University in New York and Bachelor of Architecture with Honours

from The University of Auckland. His research addresses contemporary forms of

socio-spatial transformation at the intersection of demographic change and processes

of modernization, globalization, neo-liberalization and welfare state transformation.

He is the author of Young-Old: Urban Utopias of an Aging Society published by

Lars Müller Publishers in 2015. The conversation took place via phone on

February 18, 2019.

Aging Society

Bernd

Upmeyer: In 2015 in an interview with Amanda Kolson Hurley for the Journal of

the American Institute of Architects you mentioned that you started thinking

of the impact of an aging society on cities during a trip with some friends

from university to St. Petersburg, Florida, in the 1990s. Could you explain

this experience a bit? What became obvious and intriguing?

Deane Simpson: When we were studying at Columbia in New York, a group of colleagues

and I traveled around the southern states of the US. One evening we stumbled

across a bar in St Petersburg in Florida. This was a strange experience. We

ended up in a quite intense party environment that was populated by people who

appeared to be well over sixty years of age. We sensed that we had entered into

a kind of closed society, with special social codes. We felt very unwelcome

because we clearly did not fit in there. I got the impression that there was

a certain ideal of youthfulness prevailing, but in this case, a kind of youthfulness

based upon the absence of youth. It was interesting to see how the concentration

of this age-group within this space supported particular social behavior. I

also became curious as to how some of the senior-dominated cities in Florida

seemed to produce their own realities of urban life.

BU: You

were one of the contributors to MONU’s very early issues from the years

2007 and 2008, namely issue #6 – Beautiful Urbanism with an article called

“Beyond Kitsch” and issue #9 – Exotic Urbanism with “Urbanism

of the Permanent Tourist”. In both articles a lot of ideas are already

mentioned that were later, in 2015, published in your book “Young-Old:

Urban Utopias of an Aging Society”, about which we will talk more later.

The topic of an aging society seemed to have played already a role in them and

especially in “Beyond Kitsch” the topic of theme parks was very important.

How would you describe the relationship of these articles to your book?

DS: “Beyond Kitsch”, which I wrote with Dirk Hebel, focused on an

interpretation of theming and its effects, looking at a hotel complex at Disneyworld.

Theming is a recurrent topic in the book – and an understanding of how

the entertainment-industrial complex produced space became relevant in understanding

how those logics are unfolded specifically in retirement communities. The second

article you mentioned, “Urbanism of the Permanent Tourist”, which

looked at how retirement urbanism draws on spatial formats of tourism and stretches

out time in places like Costa de Sol or Florida, was more directly drawn out

in the book...

…the

complete interview was published in MONU

#30 on the topic of Late Life Urbanism on April 15, 2019.

This

issue is supported by Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

15-02-19 // STAYIN’ ALIVE - INTERVIEW WITH FRITS VAN DONGEN

Interior of Frits Van Dongen’s newly founded

“young Amsterdam-based office”

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Frits van Dongen about “Late Life Urbanism”.

Van Dongen is a Dutch architect, who was the Chief Government Architect of the

Netherlands1 from 2011 until 2015. He studied architecture at Delft Technical

University in the 1970s. In the 1990s he realized some remarkable housing projects,

such as the “The Whale” in Amsterdam and “De Landtong” at

the Kop van Zuid in Rotterdam. During his long career he delivered over 12,000

housing units both across the Netherlands and internationally. After more than

thirty years of experience he recently opened a new office called “Frits

Van Dongen Architecten en Planners” that he describes on his website as

a “young Amsterdam-based office”. The interview took place in his

office in Amsterdam, just a stone’s throw away from “The Whale”,

on February 15, 2019.

Demographic Changes

Bernd

Upmeyer: When I was recently confronted personally with the current state of

care for the elderly, I realized that there is still a lot to improve, invent,

innovate, and discuss when it comes to the way old people in the need of care

live, particularly in a society that is ever more individualized, lacking traditional

family models in which such care used to take place.

You were born in the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch. According to a population

forecast for the year 2030 (CBS), the city’s population aged 65-74 will

increase by around 35% and the number of over-75s by around 50%. Both numbers

are comparable to trends in the entire country of the Netherlands. Do you know

how the city is reacting to these trends when it comes to urban planning?

Frits van Dongen: No, not in terms of urban planning. But I think you actually

see a reaction in the way society is developing and how a certain group of people,

elderly people - or let’s say old people - get a lot of attention. That

leads to the creation of an increasing amount of facilities due to the fact

that more public money and public subsidies are spent on them.

BU: I

believe that shared and communal forms of living, such as accommodations shared

by elderly and younger people, have an enormous potential for “Late Life

Urbanism”. You studied architecture and urban planning at the TU Delft

in the 1970s. Could you have imagined sharing an apartment with a senior at

that time?

FvD: Not at that time, no. These days, people do these things, because the general

attitude is much more developed towards this part of the society. At that time

it was a very special thing for me and my family when I became a student, left

our home, and began living on my own. And once you were there you started having

a kind of free life, getting drunk a lot, and that sort of thing. I think that

this is totally different today. I mean, when I see my kids, they are much more

social than I was at their age and that has something to do with the society

of today. They seem to be more strongly integrated and part of society, while

in my time, students were not so much part of it: we felt rather located at

the fringes of society with much less responsibility...

…the

complete interview was published in MONU

#30 on the topic of Late Life Urbanism on April 15, 2019.

This

issue is supported by Incognita’s

Architecture Trips: Discover Eastern European Architecture and Urbanism.

Find out more about MONU's supporters in Support.

23-07-18 // UNDERSTANDING URBAN NARRATIVES: WHAT CANNOT BE MEASURED -

INTERVIEW WITH CASSIM SHEPARD

Midtown Manhattan

Photo from Citymakers book by Alex Fradkin

Bernd Upmeyer spoke with Cassim Shepard about “Narrative Urbanism”.

Shepard is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Columbia GSAPP. He produces non-fiction

media about cities, buildings, and places. Trained as an urban planner, geographer,

and documentary filmmaker, he lectures widely about the craft of visual storytelling

in urban analysis, planning, and design. His film and video work has been commissioned

by, and screened at, the Venice Architecture Biennale, the Ford Foundation,

the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, and the United Nations, among many

other venues around the world. In addition to teaching at Columbia GSAPP he

has been a guest lecturer in the Cities Programme of the London School of Economics

and a Poiesis Fellow at the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University.

The interview took place via Skype on July 23, 2018.

The Power of Narratives

Bernd Upmeyer: One important

outcome of our last MONU (issue #28) on “Client-shaped Urbanism” was

the realization that in order to create better cities, we need to improve the

communication among everybody involved in the creation of cities, whether they

are clients, developers, municipalities, architects, urban designers, or the

users of cities. We believe that for architects and urban designers to make

themselves understood better, is to use the power of “narratives”,

helping them to connect not only to experts and intellectuals in the field,

but to everybody else too. Do you think that narratives have that kind of power?

Cassim Shepard: Yes, absolutely. I do think that narratives are a means towards

greater communication between the different parties that you are describing.

Narratives within urbanism are an important part of my work, especially when

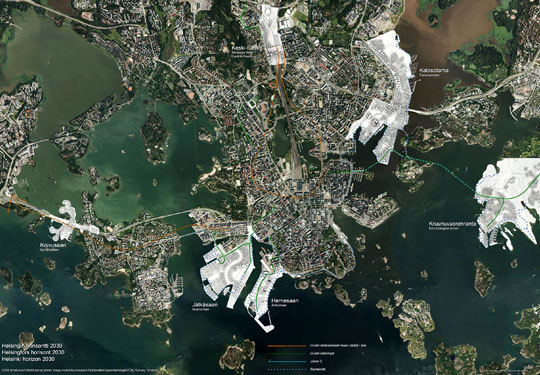

it comes to the communication between professional designers and the people